Interview with Jesse Horst, author of “Erasing Las Yaguas: Shantytown Networks and Social Reform in the Cuban Revolution, 1944–1963”

Jesse Horst works for Sarah Lawrence College as director of Sarah Lawrence in Cuba, the longest consecutively running US academic exchange program in Havana. He earned his PhD in Latin American history from the University of Pittsburgh in 2016 and was awarded the University of Pittsburgh’s 2016–17 Eduardo Lozano Memorial Dissertation Award for best doctoral dissertation in Latin American studies. His previous work has appeared in the Journal of Urban History, and he is currently finishing a book manuscript on slum clearance in Havana from 1930 to 1970. You can read his article “Erasing Las Yaguas: Shantytown Networks and Social Reform in the Cuban Revolution, 1944–1963” in HAHR 100.3.

1. How did you come to focus on twentieth-century Cuba as an area of research?

Like good research topics, it’s worked for me because twentieth-century Cuba is a time and place that generates new questions every time I find answers. Cuba has intrigued me since sixth grade, when my social studies teacher adored Fidel Castro. I grew up in South Minneapolis—tragically, three blocks from where the police murdered George Floyd this summer. It’s as far from Havana as you can get in some ways, especially the climate, but it has strange echoes: a place full of utopian politics, lots of Spanish, consciousness of US foreign policy, class divisions that map onto urban space, racial hierarchies that disappear from one angle and explode from another.

I went to Cuba for the first time in 2004 on a wonderful study abroad program led by Jeane DeLaney at St. Olaf College. What intrigued me about Cuba intellectually was how it could render familiar issues unfamiliar. It allowed me to consider things that I always cared about—like housing, race, or radical politics—from new angles. I think that approaching Cuba as a place that’s familiar in some ways while respecting its uniqueness helps to draw out interesting questions.

Ultimately, I fell in love with Cuba because of its contradictions. They matched up with contradictions I saw in myself. Now that I’ve spent many years there, both for research and work, Havana is my favorite city in the world. It’s become home.

2. Your article opens with a quote from Fidel Castro stating that “we have no shantytowns here” in Cuba. Did this denial of urban informality pose any challenges in reconstructing the story of Las Yaguas and the other shantytowns discussed in the article?

I thought that was such an interesting quote. It is a denial of urban informality, but it’s a very particular kind of denial. The context was a speech in the mid-1980s where Fidel was explaining that the government would send family doctors to…where? He wanted to say to shantytowns, but he caught himself. “Areas that need them most,” he said. It was an affirmation that the government was addressing underresourced areas, but without naming the social and economic barriers that traditionally marked them. Part of this was aspirational—by not naming those barriers, I think he was seeking to not call them into being or legitimize them.

Of course, that erasure hasn’t only been aspirational. It’s made the type of housing-based politics that I write about in Las Yaguas very complicated. During the 1990s and 2000s, when Cuba was facing an incredibly hostile situation internationally, precarious housing also grew, especially in Havana. My impression is that it was intensely difficult to research at certain points.

I’m not a journalist, I’m a historian, and that has made my work much easier. Even though 1959 is uniquely sensitive for something that’s more than six decades past, it’s still the past. My work has become much less sensitive because of really talented Cuban scholars who have illuminated housing inequality in the present—not as a way to weaken the Cuban government vis a vis the US, but as a way to make it more responsive to its citizens. I’m talking about Mayra Espina Prieto, Pablo Rodríguez Ruíz, Luisa Iñiguez, Gina Rey, Reinier Moreno, the late Mario Coyula, and many others.

Today, I would say that there is not much denial of deficient housing in Havana. Silvio Rodríguez, the classic singer of the Revolution, has done a major concert series to highlight neighborhoods with precarious housing in Havana. Alejandro Ramírez made a beautiful documentary about it, Canción del Barrio, with a great accompanying book by Monica Rivero, Por todo espacio, por este tiempo. Journalist Mónica Baró Sánchez has done amazing investigative reporting of lead poisoning in vulnerable areas. Michael Sánchez Torres does great community advocacy in los Pocitos with Proyecto Akokán. Popular Cuban films like Conducta and Habanastation have even brought housing deficiencies to the big screen. And every Sunday, if you watch the popular Cuban police drama Tras la huella, a number of plots revolve around busting crime rings in Havana shantytowns.

Consciousness is there. Financing, especially as the US embargo continues, is much more complicated.

3. Your article looks to continuities in slum clearance plans between the Batista and revolutionary regimes. How does this historiographical move allow new insights into Cuban history?

I’ll never forget my first summer of research, when I sat in the Library of Congress in Washington DC and read the entire run of Arquitectura (a pre-1959 journal). This was a very stuffy, elite journal, but I kept finding rhetorical elements that fit language I had always associated with 1959. It caught me off guard. I don’t mean rhetoric that called for Batista’s overthrow—there was none of that. I mean the rhetoric of urban planning, of governance. How could this be? In fact, it was not that these elite guys were all so progressive, or that Revolutionary leaders were all so stuffy—it was that the urban poor had managed to get their voices into the political system in certain ways. This is not an isolated case.

What’s happened in the historiography of 1950s Cuba is that it’s been very easy to forget the interesting things that were happening in politics and society beyond antigovernment protest. Historians have lost track of institutions and practices like health care or religious freedom or economic planning in those years, each of which has a particular, unique history. Whether these can be considered origins of the specific events that led to Batista’s fall from power is very doubtful—and yet they mattered deeply to the course of Cuban society in the years that followed.

There are good reasons for this oversight. The Batista government ended up being very brutal and clumsy, and the protest against it ended up sparking one of the best-known events in twentieth-century Latin American history. But what do we lose if we look to the origins of Cuban society in the 1960s purely in terms of a specific revolutionary movement in the 50s, however popular it ended up being? What do we lose if we solely focus on that angle, to the exclusion of all others? In my view, we lose quite a lot. My own particular argument in this article is that we lose the voices of the urban poor, of Las Yaguas residents, who managed to shape urban policy on a national scale before 1959 against very difficult odds.

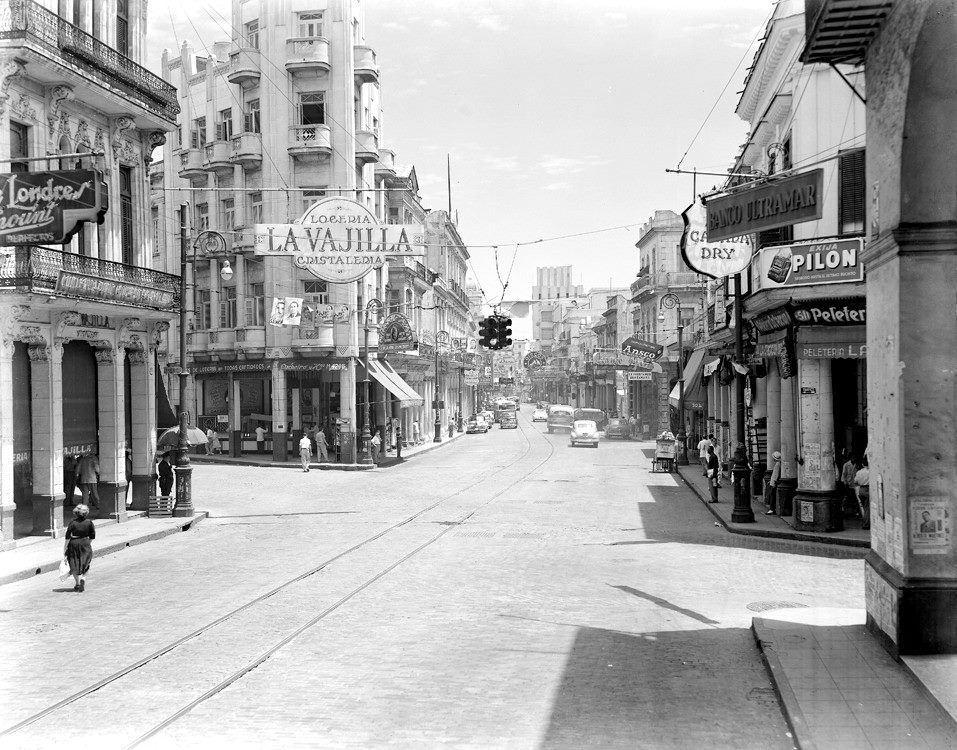

Newsreel footage from April 1950 after a fire in Las Yaguas.

4. How does the experience of Cuban shantytowns compare to shantytown communities throughout the Americas?

This is a great question (they’re all great questions, by the way!). There are so many similarities across the Americas and their history needs to be explored. I began researching after reading Brodwyn Fischer’s magisterial book on Rio de Janeiro, A Poverty of Rights, which showed me exactly what to look for.

The similarities are not coincidence. Going back to the 1930s, many technocrats and urban planners actively discussed their experiences with shantytown policy at inter-American conferences and other professional meetings. So there was a shared vocabulary to be sure. But each country ended up with key differences and Cuba looked especially different.

What was striking about Cuba before 1959 was how the national political system took over shantytown policy from very early on. In Brazil, well into the 1950s, urban informality was primarily an issue for the courts. In the wake of the 1940 constitution in Cuba, though, it became an issue of national policy. Not in the sense that just one politician or one party felt pressure to intervene, but that politicians across the spectrum faced a similar cocktail of dilemmas. In Peru or Chile, for example, the issue was also political, but in a more partisan way. I’ll try not to overstate my case, but I think this mattered to why 1959 looked the way it did.

Housing policy was nationalized to a much greater extent after 1959, but it’s ironic that as Cuba moved away from hemispheric norms in many ways, it actually drew closer to the inter-American consensus on urban and regional planning. Many of Cuba’s policies in the 1960s looked more like Brasília than Moscow. By controlling the economy, officials were better able to put certain ideas into practice. Growth in the capital slowed way down, and with it, the growth of shantytowns.

5. How does this legacy of shantytown community inflect urban informality in Cuba today, if at all?

The type of community and grassroots-level democracy that sometimes existed in Las Yaguas rings true to Cuban culture all the way up to this very moment. Housing in the capital is a contentious issue today, and being a migrant from outside Havana can generate stigma. At its best, though, Cuban society still holds to the belief that all citizens deserve decent housing. People care about each other. Just as it did in Las Yaguas, that belief remains something that informally housed communities can leverage as they try to carve out the lives that they hope for.

In a more direct way, I think the explosion Afro-Cuban religious practice over the past two or three decades speaks to the legacy of close community along historically disadvantaged geographies. A number of areas that are recognized for their religious power today began as informal settlements. And Santeria is now a global religion. More and more, people are recognizing it as an irreplaceable contribution to world culture.

6. Read anything good recently?

Always! The best thing I’ve read recently was Los estratos, a novel by Juan Cárdenas about the social geography of the Pacific Coast of Colombia. “Los estratos,” of course, are the economic categories by which neighborhoods in Colombia are classified. The novel is stunning, sort of Nestor Canclini meets Amores Perros, with a bit of Stephen King. I couldn’t put it down.

I also loved Marixa Lasso’s recent book, Erased, about the forgotten eradication of vibrant towns across the Panama Canal Zone. It gets at some of the issues I’m exploring in my own work in a fairly brutal context. Recently I’ve been teaching about Afro-Cuban religions, so I’ve also been going through commentary on the visual arts of Belkis Ayon, which is just too powerful for words.

On my quarantine nightstand is El amor en los tiemos de cólera—I know this will be shocking for your readers but it’s really good.

Top image: Havana street at night. Photograph by Thomas_H_foto. Licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0. (Find the original here.)