Interview with Isadora Moura Mota, author of “Other Geographies of Struggle: Afro-Brazilians and the American Civil War”

Isadora Moura Mota is assistant professor of history at Princeton University. Her scholarship focuses on modern Brazilian history, comparative slavery, abolitionism, literacy, and the African diaspora to Latin America. Mota’s first book, An Afro-Brazilian Atlantic: Slavery and Anglo-American Abolitionism in the Age of Emancipation (University of Pennsylvania Press, forthcoming), explores the role of Afro-Brazilians in shaping the history of abolition in the Atlantic world. You can read her article “Other Geographies of Struggle: Afro-Brazilians and the American Civil War” in HAHR 100:1.

1. How did you come to focus on nineteenth-century Brazil as an area of research?

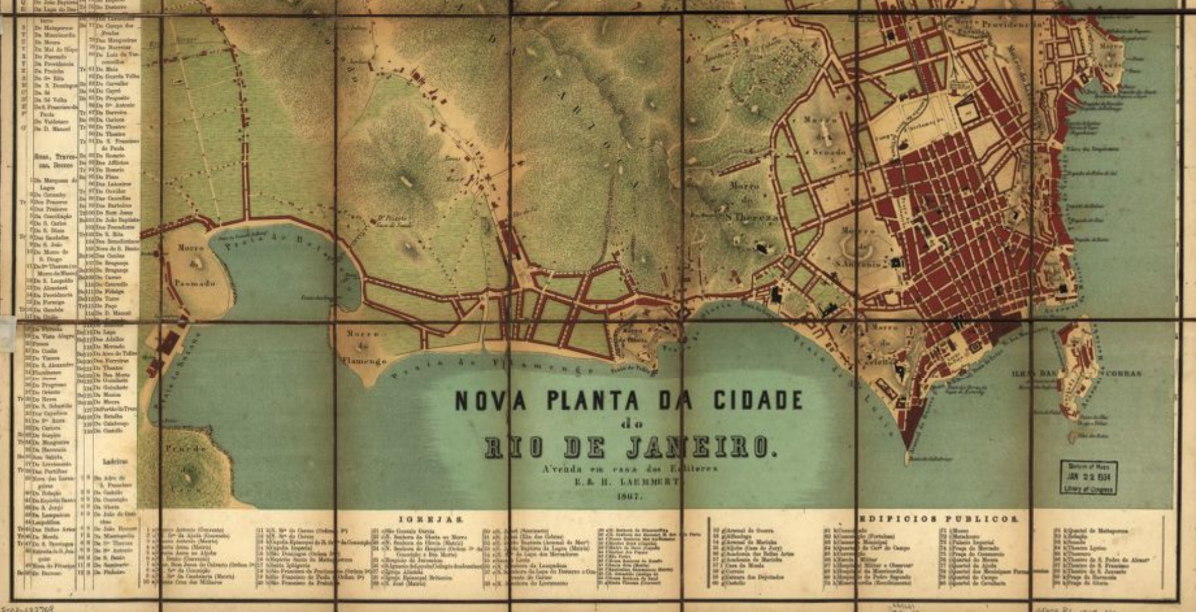

I grew up in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, always surrounded by nineteenth-century history and intrigued by the legacies of slavery in the city. My research experiences in college, though, initially directed me to the early twentieth century. I was lucky to become a research assistant to professor Flávio dos Santos Gomes at UFRJ, where I studied Brazil’s first black political party in the 1930s – the Frente Negra Brasileira – and assisted in the organization of Abdias do Nascimento’s personal archive. I was so inspired by the experiences of antiracism activists in Brazil that I decided to go back into the nineteenth century to better understand black struggles for freedom in time. Once I got to lose myself in the manuscript documentation held in the Brazilian National Archives, I never turned back and eventually set out to write about nineteenth-century quilombos and slave revolts. Now, more than an area of research, the nineteenth century is the lens through which I understand a country where black emancipation remains an unfinished process.

2. How did you develop what you call the “Afro-Brazilian geopolitical imagination,” and how does this concept help us understand Afro-Brazilian uprisings in Maranhão?

The idea came from the need to articulate the expansive worldview of the enslaved in Brazil. They were such avid readers of the nineteenth-century political landscape! When encountering their references to the Haitian Revolution, South American republicanism, or the American Civil War, in the case of Maranhão, I kept asking myself: What can we call these perceptions that allow us to think about Brazil as a place connected to the world through the experiences of the disenfranchised? Geopolitical imagination or literacy is what I thought accounted for the kind of critical consciousness that empowered the enslaved to move within or against shifting geographies of slavery and freedom. In the 1860s, the concept helps us understand why Afro-Brazilians rose up at the sight of North American warships in Maranhão. Enslaved communities and freedpeoples in São Luís expected nothing less than military cooperation from foreigners involved in what they envisioned as an abolitionist conflict. Their uprisings show that Brazil was also a battleground of the American Civil War, a conflict that reverberated in all the corners of the African diaspora.

3. Is there an overarching story of abolition in the Atlantic world, and how might Brazil fit into that narrative?

Looking into the world from Brazil, abolition still sounds like a very Anglocentric story. If there is an overarching story about emancipation in the nineteenth century, it is the narrative of Anglo- American antislavery unfolding within a global capitalist order in which Brazil is, at best, secondary. The country is probably better known as a slavery holdover in the age of abolition rather than a producer of black claims for self-determination. This is both a question of emphasis and the optics of the history as a discipline. When we think about an antislavery movement, who are the protagonists, where do we look for them, and what range of experiences are we talking about? Studying the activism of the enslaved living in the longest-lasting slave society in the Western world certainly changes what Atlantic abolition looks like. If we center Afro-Brazilians as heuristic agents in their own right, then a different version of internationalism emerges. Ultimately, their story recasts nineteenth-century abolitionism as more than the cause of Anglophone reformers, diplomats, or modernizing elites to become also a radical grassroots movement originating in South America.

4. What did Raphael Semmes of the CSS Sumter hope to accomplish by “internationalizing” the American Civil War through attacks on Northern ships in foreign waters? How did this tactic affect Semmes’s dealings with Brazilian officials and ports, and how did David Dixon Porter (commander of the USS Powhatan) and Brazilians react?

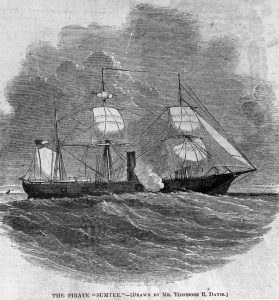

Like other Confederate ship captains during the Civil War, Semmes targeted Union merchant ships traveling abroad. He expected the government of slave nations like Brazil to express a sense of solidarity with the Confederate cause and often admonished foreign authorities that the Union represented a threat to the stability of slavery everywhere in the Americas. Brazilian officials were then caught in a difficult position: despite their general proslavery inclinations, they were supposed to abide by Dom Pedro II’s declaration of neutrality in the war. Brazil ended up embroiled in a series of diplomatic incidents with Washington after confrontations between Union and Confederate vessels took place along the Brazilian coast, involving loss of life on both sides. In 1861, David Dixon Porter came to Brazil in pursuit of the CSS Sumter and expressed disappointment at the lukewarm welcome that the USS Powhatan received in Maranhão. He believed Brazilian authorities would remain neutral in their dealings with North Americans but soon learned that that was an impossible proposition in a country defined by African slavery. Most Brazilians remained unsure about what to make of the US Civil War until the mid-1860s, when it became clear that the conflict would deal a blow on Atlantic slavery. The enslaved, however, envisioned the presence of North American ships since very early on as a sign that emancipation was imminent.

5. What sources exist on slave flight to Union ships, and what might these sources reveal about Afro-Brazilian communication networks, discourses on abolition and (hemispheric) freedom, or Brazilian reactions to slave flight?

There are many sources about the subject, including fugitive slave ads and slaveholders’ letters published on Brazilian newspapers, judicial records documenting the prosecution of escaped slaves, and diplomatic correspondence detailing negotiations between the Brazilian and American governments. When read against the grain, these archives show that Afro-Brazilians considered Union ships as a node in Atlantic seafaring escape routes, which connected black networks of communication and experience all over the African diaspora. The enslaved perceived Union ships – especially whalers – as free soil spaces where they could claim either freedom or at least some degree of protection from Brazilian authorities. As a result, the latter carefully patrolled the country’s coast, denouncing Union captains as “instigators” of slave flight. Ships were also main purveyors of news in the nineteenth century: crews and travelers exchanged information with those ashore, delivered newspapers, and carried letters throughout the Atlantic. That is how the American Civil War first reached Brazil, spreading hope in enslaved communities and fear among slaveholders and state officials committed to the continuity of slavery.

6. Read anything good recently?

I have just finished Ganhadores: A greve negra de 1857 na Bahia, by João José Reis, a beautiful book that explores the vibrant urban culture of enslaved and free street workers in Salvador. Mostly African and Nagô, they led one of the first strikes in Brazilian history. I am also puzzling over the meanings of diasporic warfare in Vincent Brown’s Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War.

In these challenging times we live in, fiction has become even more important for me as a way of coping with and understanding the present. I have been reading Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah alongside Olhos d’Água, a collection of short stories by my favorite contemporary Brazilian writer, Conceição Evaristo.

Top image: Nova planta da cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 1867. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Public Domain. (Find the original here. Image was cropped, and MB size was adjusted.)

Second Image: ‘, , 1862. Courtesy of the . Public Domain. (Find the original here.)

Third Image: , Photo #: , c. 1860-1869. Courtesy of the . Public Domain. (Find the original here.)