Interview with Ryan M. Alexander, author of “The Fever of War: Epidemic Typhus and Public Health in Revolutionary Mexico City, 1915–1917”

Ryan M. Alexander is associate professor of history at the State University of New York College at Plattsburgh. He is the author of Sons of the Mexican Revolution: Miguel Alemán and His Generation (University of New Mexico Press, 2016). His research interests range from political violence and popular memory to circus culture and disease epidemics. You can read his article “The Fever of War: Epidemic Typhus and Public Health in Revolutionary Mexico City, 1915–1917” in HAHR 100:1.

1. How did you come to focus on twentieth-century Mexico as an area of research?

Somewhat by accident. In college history classes, I became interested in revolutions and social movements. I went to Cuba for a semester abroad, mainly because I had some rudimentary training in Spanish, and it changed my perspective in profound ways. It was also the beginning of my interest in Latin America. In graduate school, I hadn’t initially intended to study Mexico, but I got pulled toward it by the large and active community of students, scholars, and activists working on Mexico all around me while I was at the University of Arizona. I was fascinated by life near the US-Mexico border in Tucson and fell in love with Mexico City. Most importantly, I found meaning and clarity through my engagement with Mexico’s history. It just built from that.

2. How does a deeper understanding of the typhus epidemic shift our understanding of the development of public health initiatives, especially in relation to indigenous communities?

Some would say that it doesn’t tell us much, given that it was a relatively brief epidemic, and granted, it doesn’t foretell everything that would happen in the decades after 1920. But I think in some ways, the fact that the epidemic was so brief, unexpected, and deadly, and consequently that it prompted such a knee-jerk response, might actually clarify exactly where indigenous people stood in terms of official priorities and popular perception. There is no question whatsoever that indigenous people, while exalted (if also homogenized) in official revolutionary rhetoric, did not find a remedy to centuries of exploitation and inequality in the twentieth century, whether in terms of public health or education or anything else. I think the 1915 typhus epidemic, which drew out long-standing stereotypes of indigenous people, provides some glimpse of what was to come.

3. Why did you choose to focus on the 1910–20 armed phase of the revolution to study public health? How do your findings for this period expand our understandings of the revolution?

As I delved into the project, I came to realize that there was a good deal of work already done on the period before 1910 (particularly within the Porfirian modernization paradigm) and after 1920 (particularly within the intertwined frameworks of nation- and state building), but the literature on the decade of armed struggle usually contained nothing more than passing references, or at best an occasional descriptive paragraph or two, on public health and disease. Scholars have so meticulously pieced together the political and social dynamics of the revolutionary movement itself but have somehow treated health and disease like background noise. So that’s what I wanted to address. I didn’t want to follow a strictly state-centered approach, nor did I entirely want to shun that. Rather, I aimed to write something like a social and political history of the epidemic.

4. How does studying the public discourse surrounding the epidemic contribute to an understanding of social and economic issues like poverty or inflation?

If you had asked me this question even three months ago, I’d have given you a relatively predictable answer about how, in spite of the public pronouncements of unity that they tend to prompt, disease epidemics in fact tend to exacerbate structures of inequality. That was true during the typhus epidemic, and it’s still true today. The difference is that it’s right in front of us at the moment, so it’s much less abstract, meaning it’s also easier to see and harder to deny. Fact is, those at the bottom of the income ladder suffer more, those near the top less, and those at the very top often exploit crisis for gain. COVID-19 also helps to clarify the importance of intersectionality—not only do poor people, whose jobs often cannot move to an online format or whose access to health care is usually far less certain than their wealthier counterparts’, suffer disproportionately, but we can see that women face more peril in their professional lives and, worse still, that people of color die at higher rates. We can see similar dynamics at work in the typhus epidemic and in many other historical examples.

5. Why did you choose to focus on José María Rodríguez, and what did you find most interesting about his concern for individuals like María Sarabia or Alberto Sánchez (pp. 77–88)? What do these anecdotes tell us about Rodríguez and the Superior Council of Public Health?

I tend to approach history by trying to be one part social scientist and one part humanities scholar. The social scientist in me wants to understand how social structures and institutions govern human behavior, and how we might identify patterns and variables over time that can in turn create models for understanding how people operate. The humanities part of my brain likes compelling narrative, and that begins with understanding the unique, idiosyncratic nature of human motivation. So, one of the things I always try to do is have some kind of biographical component to whatever I’m writing. I think history is fundamentally more interesting and relatable this way. You wouldn’t read a novel without a protagonist; it is the empathy with the protagonist that allows the reader to see a different world, or at least the same world through different eyes. It’s no different with history. So, in this case, that person was Rodríguez. He’s the focal point of all the issues I explore, such as inequality or race politics or regionalism, and all the other people in the narrative, whether they are volunteer doctors or prisoners or bureaucrats, orbit around him. And, at the risk of sounding a little glib, I can’t help but see the parallel with Anthony Fauci, as the face of the federal government’s COVID-19 response.

6. Read anything good recently?

Plenty, but the book I’ve read recently that most closely relates to what has been discussed here is Tommy Orange’s debut novel, There, There. It follows the lives of Native American people in and around Oakland, California. Although the book has a healthy dose of humor, ultimately it’s tragic—the plight and suffering of many of the characters is gut-wrenching. The fact that their suffering plays out in an urban setting in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, rather than in a more familiar context like the nineteenth-century Western frontier, makes it all the more captivating. There is a sense that the people in the story suffer a kind of double invisibility – invisible in the common memory and the dominant historical narrative, and invisible today as so-called “Urban Indians” – and that this lack of visibility can explain their plight.

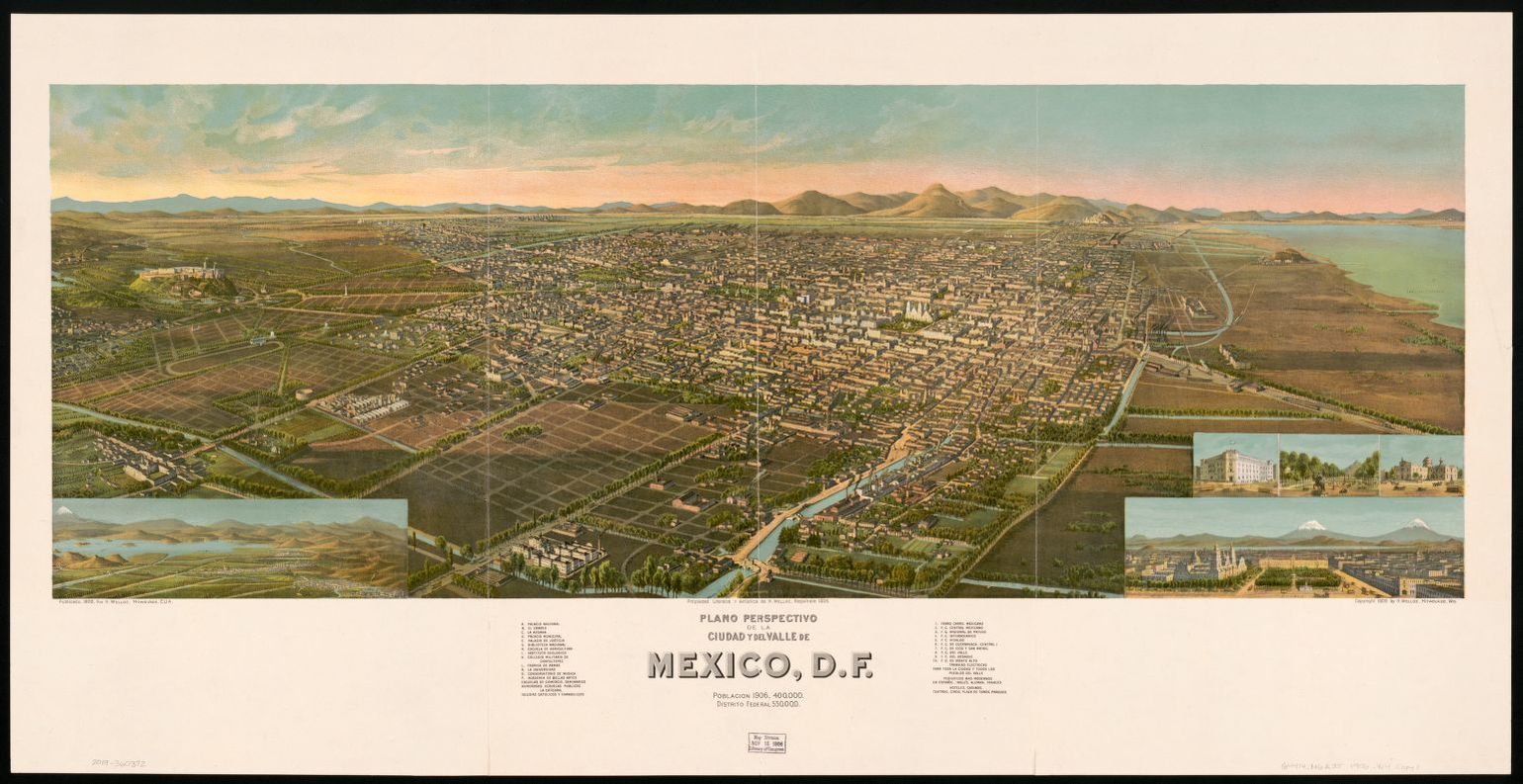

Top image: Plano perspectivo de la ciudad y del valle de Mexico D.F., 1906. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. Public domain. (Find the original here. Image MB size was adjusted.)

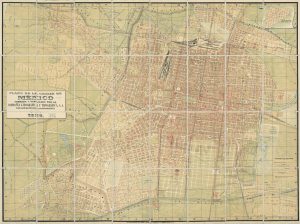

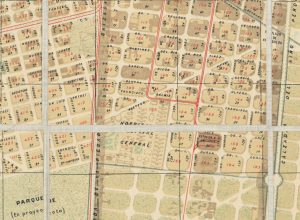

Second and Third Image: Plano de la Ciudad de México, 1917, and Detail. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. Public domain. (Find the original here. Image MB size was adjusted.)