Interview with Sueann Caulfield, author of “Jesus versus Jesus: Inheritance Disputes, Patronage Networks, and a Nineteenth-Century African Bahian Family”

Sueann Caulfield is associate professor of history and associate professor in the Residential College at the University of Michigan. Her publications include In Defense of Honor: Sexual Morality, Modernity, and Nation in Early Twentieth-Century Brazil (Duke University Press, 2000), the coedited volume Honor, Status, and Law in Modern Latin America (Duke University Press, 2005), and various articles on gender and historiography, family law, race, and sexuality in Brazil. You can read her article “Jesus versus Jesus: Inheritance Disputes, Patronage Networks, and a Nineteenth-Century African Bahian Family” in HAHR 99.2.

1. How did you come to focus on Brazil as an area of research?

I became interested in Latin America in 1979 through a high school history project on the Sandinista revolution. In the mid-1980s, while in college at Berkeley, I studied abroad in Costa Rica and spent time in Nicaragua. Returning to Berkeley, I decided to study Latin American history and became active in student movements against US imperialism. I took classes from Tulio Halperín Donghi and Linda Lewin, including Lewin’s History of Brazil class senior year, which changed my life! I remember clearly her lectures on marriage and naming strategies among elite Brazilian families. After graduation, I worked as a Spanish-English interpreter to save up for a trip to Brazil. I ended up staying in São Paulo for eight or nine months, where among other activities, I worked at a bar in Bixiga. While I was in São Paulo, someone recommended the book Rio Claro: A Brazilian Plantation System, by Warren Dean, and after reading it, I decided to apply to the MA program in Latin American Studies at NYU, where he taught. Warren Dean was a truly remarkable historian, mentor, and human being, with a contagious passion for Brazil and its history. I wanted to continue learning from him, and I wanted a chance to return to Brazil, so I applied to continue on for a PhD in Brazilian history.

2. Your new HAHR article revolves around litigation over inheritance between an illegitimate child and a former slave. How did you discover this unique case?

I found this case many years ago while doing exploratory research in the Bahian state archive on family disputes over inheritance and child support. Not surprisingly, there are hundreds such cases in the archives; in Bahia, I read several dozen from the early and mid-twentieth centuries. This one was first brought to my attention by a fellow researcher who was seated next to me one day. Unfortunately, I did not record her name, so I cannot thank her properly! At the time, I did not think the case was relevant to my project, since I was working on the twentieth century. I later discovered through a Google search that large portions of the case had been published in a Bahian law journal, and I looked for the original again. It stood out because it was the last in a series of Supreme Court cases that were discussed in jurisprudence on the process of “legitimization,” which had been a royal dispensation prior to independence and was seen by leading nineteenth-century jurists as anathema to liberal principles. The case is also unique because it involved a large estate owned by an African-Brazilian man. This led me to analyze it within the context of the historical literature on the small but significant black elite in the nineteenth century. The case has also led me to include a chapter on the nineteenth century in my larger research project.

3. Your article does an amazing job of tracing the life histories and cultural worlds of the figures involved in this litigation. What challenges did you face in reconstructing these, and how did you address these challenges?

One of the early challenges was the overwhelming quantity and density of manuscript documents, including several lawsuits and postmortem inventories that were each hundreds of pages long. I had not previously worked with nineteenth-century script, and the learning curve was steep! After making it through this first bunch of documents, the next big challenge was that I was able to spend only short periods of time in Bahia. This kind of research is not possible to do all at once; frequently, I would get a hunch, find a lead, or realize I wanted to look for new information only after I was back in Michigan and rereading documents, or after I had completed a draft of the article. I spend many hours poring over online resources such as FamilySearch.org, where I found digitized copies of many ecclesiastical records, and the National Library’s hemeroteca digital, where I was able to find a number of relevant newspaper articles and entries in state almanacs by searching for names of various individuals who appeared, even as minor characters, in other documents. Some of what I discovered about minor characters led me to understand, for example, that Conservative Party politics played an increasingly important role in social networks in Brotas (the African-Brazilian parish where the man at the center of the article built his fortune). This kind of research often resembled searching for a needle in a haystack, and it was often a challenge to recognize when it was time to give up! Once I had gathered a sizable collection of needles, it was challenging to resist the impulse to describe every one of them in the article. I learned a great deal about several individuals whom I ended up having to cut out of the story. It was hard to let go of them but necessary for narrative coherence.

More important than the electronic resources were the personal ones. I was extremely fortunate to be able to rely on both the support and the previous research of several Bahian historians. The first was Jacira Primo, a phenomenal research assistant who had been a graduate student at the Federal University of Bahia working with Professor Gino Negro. Later, I discovered (through a Google search) the blog of historian and archivist Urano Andrade, who was working with Professor João Reis in 2018 to digitize several collections at the Bahian State Archive. Urano was crucial at the end of the process, when I wanted to follow up on a few hunches that came to me after I had finished writing what I thought was the final draft. Urano emailed me freshly digitized documents that helped me fill out the period of the 1820s, and he even helped me transcribe some of the more difficult ones. An example is a prenuptial agreement that allowed me to give some texture to the life story of one of the minor characters in the story while illustrating an underlying theme: the economic concerns that accompanied marriage between unequal partners and the desire of even relatively young property owners to maintain control of their estate after their death. Among the documents I was looking for was the correspondence of a justice of the peace that had been used by João Reis thirty years ago in a wonderful article about the repression of candomblé. When Urano was unable to find some of the letters with the old archival notations, I contacted João, who sent me photographs of his dog-eared handwritten notes, taken more than three decades earlier! João had already read an early draft of the article and offered very helpful suggestions, and I also relied heavily on his article and on many other works he has published on Bahian history.

As is evident in the footnotes, Linda Lewin’s 2-volume work on legitimacy law was also critical, and her generous comments on an early draft helped me rethink the legal analysis. Other colleagues who read and commented on the manuscript also helped me with specific challenges as well as the larger task of telling a coherent story of one family and using it to reveal broader historical dynamics. Space limitations prevent me from mentioning all of these colleagues here, but each person I thank in the acknowledgments helped me address challenges in substantive ways.

4. What resonances do the gender and racial dynamics exposed in this nineteenth-century litigation have in Brazil today, if any?

The dynamics that arose in this case reflect the complex ways that the dual logics of patriarchy and slavery inflected social and financial relationships within families, households, and communities in nineteenth-century Brazil. Today, the law no longer sustains either slavery or patriarchy, but both institutions have left powerful legacies. Struggles to combat these legacies played a central role in defining both citizenship and the family throughout the twentieth century. In an example that is especially relevant to the litigation I analyze in this article, movements to eliminate discrimination against children born outside formal marriage became part of a clearly articulated feminist campaign to combat patriarchy in Brazilian law in the 1970s. Brazilian feminists’ antipatriarchy discourse emerged in dialogue with feminist movements around the world, but it also converged with longstanding processes within Brazilian courts. Beginning in the 1920s, the rights of unmarried mothers and their children expanded through case law and public policy, a process that played out in fits and starts in labor and family courts. Together with the feminist movement, this expansion of rights played a key role in the 1988 Constitution’s reconceptualization of the legally constituted family as an institution that fosters equality and human dignity. Illegitimacy became obsolete as the constitution formally recognized a plurality of family forms and mandated equality between spouses and among children. Thirty years later, however, activists continue to struggle to dismantle racial and gender hierarchies that limit access to constitutional guarantees of equality and dignity for all Brazilians.

5. Is the microhistory contained in this article part of a broader project? If so, would you mind discussing this broader project briefly?

I am working on a book on the history of legitimacy in Brazilian family law from the nineteenth century to the present. The first chapter discusses how the ideology of slave masters’ paternalism was used to disguise a pattern whereby fathers raised their illegitimate children by enslaved women to occupy an indeterminate position on the social hierarchy, above that of slaves but below that of legitimate children. I then use the case analyzed in this article to illustrate how nineteenth-century jurists’ debates over legitimacy law influenced the construction of liberal principles that justified the perpetuation of inequality (between husbands and wives and among children) in twentieth-century family law. The book’s subsequent chapters address the ways litigation and public policy regarding the right to the benefits of family membership contributed to the transformation of family law over the twentieth century, culminating with the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2013 and the subsequent expansion of reactionary movements to resuscitate patriarchy and narrow the definition of family.

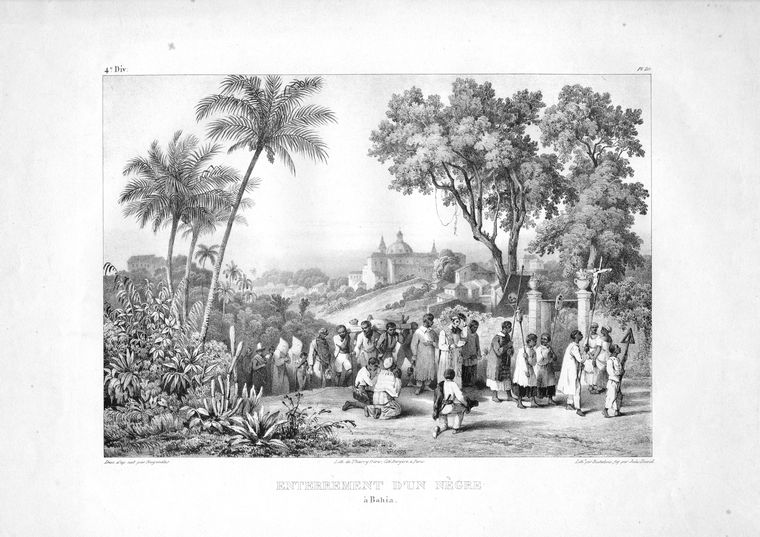

Top image: Photograph of Salvador, Bahia, between 1912 and 1919. Reuse of image courtesy of BNDigital. (Find the original here.)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.