Open Forum on Archives and Access: The DFS Controversy

Curated by Jocelyn Olcott and Sean Mannion, Duke University

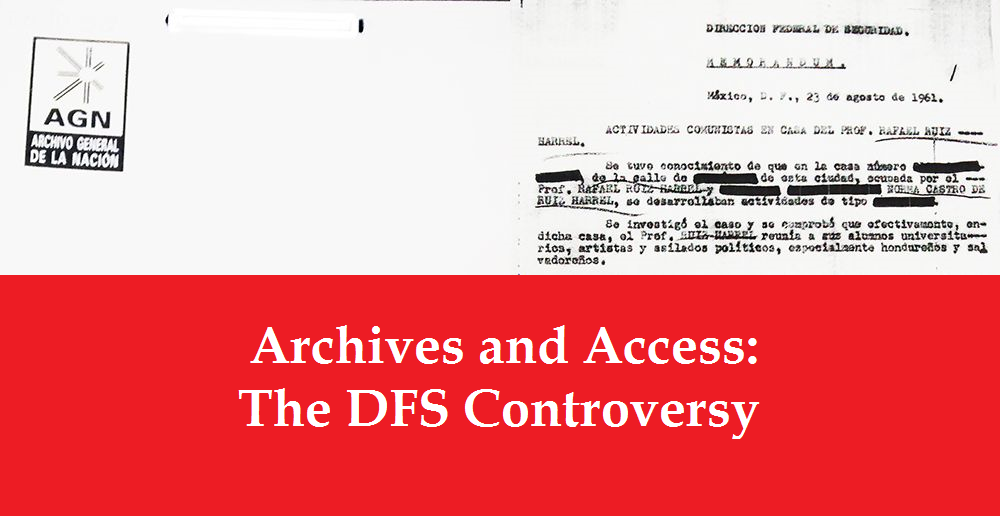

Ever since their opening to the public in 2002, the archives of the Dirección Federal de Seguridad (DFS) have proven to be both an invaluable trove for researchers and a political lightning rod. In January of this year, new restrictions on access to this source were announced, threatening a burgeoning historiography on Mexico’s dirty war and on the country’s social and political movements from the 1950s to the 1980s, in addition to raising broader questions about freedom of scholarly inquiry and open access to state records.

The closure raised questions about the role that researchers should play in ensuring continued access to public records, and HAHR has invited a number of leading historians to open up a conversation about the context for and ramifications of these new restrictions on access to the DFS archives. We invite all readers to weigh in on this debate.

Commentary by Kirsten Weld

Documents and archives are indispensable tools of state power; they are, as Ann Stoler puts it, “technologies of rule.” Their contents, compiled by bureaucrats and functionaries over time, make citizens legible to authorities in myriad ways. Their form, meanwhile, reveals how government institutions think and act, and what categories of knowledge they prioritize.

Beyond this, however, state archives also serve important symbolic and performative functions. In their information-gathering practices, resource allocation, and archival access policies, governments send messages to their citizens. They communicate a commitment to transparency, or a lack thereof. They make arguments about history, nationalism, and national character. They demonstrate a willingness to diverge from the activities of past regimes, or they betray continuismo, a desire to uphold previous paradigms. Archives both reflect and constitute power, and the way that states manage archival access is designed to send a message about where citizens stand and how—or whether—leaders might be held accountable for their actions.

One way that states can signal their intent to break from the past is to open the files of former repressive regimes or government agencies. The transformation of the Stasi’s archives into a citizen resource, for example, was one of the core components of German reunification after the fall of the Berlin Wall. And in the aftermath of Latin America’s so-called “dirty wars,” many democratic administrations have found opening the archives of their countries’ Cold War dictatorships to be not only politically expeditious, but critically necessary to the slow and fraught work of peacetime reckoning. Those records have, in turn, been used to identify the remains or fates of disappeared persons, prosecute war crimes, research truth commissions, spark national debates, and lustrate institutions. Sometimes voluntarily, yet more often than not at the exhortation of mobilized publics, governments across the Americas, including in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay, have made commendable strides in liberalizing access to Cold War surveillance records. In so doing, they have tried to wrest their countries’ futures from the grip of bloody pasts.

For a while, Mexico was also on that list. Whatever the motivation for opening the records of the Federal Security Directorate (DFS) in the early 2000s—a cynic might see it as an effort on the part of the then-ruling PAN party, headed by Vicente Fox, to embarrass the PRI—the result, in concert with the 2002 Transparency Law, was transformative. Finally, journalists, researchers, and families of the several thousand desaparecidos from the country’s dirty war could investigate, discuss, and illuminate what was arguably the darkest period of the PRI’s long hold over Mexican politics. Books, op-eds, articles, and spirited public conversations ensued.

But by closing the DFS records once more—in an echo of the George W. Bush administration’s campaign, in the mid-2000s, to reclassify tens of thousands of previously declassified U.S. documents—the PRI sent a different message: that it was not, in fact, invested in breaking with the capricious and authoritarian practices that have traditionally been the party’s trademark. PRI officials would certainly not be wrong to fear that the gruesome abuses of power chronicled in the DFS files could affect their chances in the 2018 presidential election, not least because the election will mark the 50th anniversary of the Mexican dirty war’s most emblematic atrocity: the 1968 massacre at Tlatelolco. Yet in allowing uncertainty around the access conditions of the DFS files to build, thus demonstrating the archives’ ongoing vulnerability to political gamesmanship and the PRI’s continued preference for obscurantism over accountability, the Peña Nieto government may have caused itself more damage than it has averted. That said, the urgency of the DFS files’ status, as the researchers who know their contents and the families of the disappeared can attest, goes well beyond questions of short-term political advantage.

Those interested not only in keeping the DFS files accessible, but in insulating all Mexican government archives from the self-serving impulses of particular regimes, might look to Guatemala for inspiration. There, justice activists have labored for a decade to protect the voluminous archives of the country’s now-defunct National Police from powerful enemies, a climate of official impunity, and the inadequacies of the corresponding state institutions—and, against all the odds, they have been remarkably successful. Why? Because they marshaled substantial material and moral support from international allies, mustered public pressure, pushed for a neutral legal framework that would insulate the archives from political manipulation, enjoyed the engagement and solidarity of a wide array of Guatemalan NGOs, and obtained access to the best practices and accumulated wisdom of organizations elsewhere that work to safeguard similarly sensitive archival collections.

Above all, however, Guatemalans were able to save the National Police documents because they realized that fighting for archival access was not, in fact, separate from the seemingly more pressing political concerns usually at the forefront of progressives’ minds. Rather, just as archive-power is an essential element of state power, so too is archival activism an essential element of democratic activism. Mexican citizens and their international allies must continue to agitate against state secrecy, because the way a state treats its archives speaks volumes about the way it treats its citizens. Where files can be made to vanish, so too can people.

Kirsten Weld, Harvard University

Commentary by César E. Valdez

Batallas por la memoria, episodio México.

El 11 de marzo de 2015 el periódico La Jornada publicó un reportaje titulado “Canceló Gobernación acceso directo a los archivos de la guerra sucia”. La noticia suscitó comentarios y reacciones que oscilaron entre la incredulidad y la indignación. Unos cuantos días más tarde el diario El Universal también dio cuenta de “los cambios en los criterios de consulta” en dicho acervo. Algunos investigadores ya habíamos escuchado rumores y constatado que “algo” estaba cambiando en la Galería 1 del Archivo General de la Nación que resguarda los documentos de la extinta Dirección Federal de Seguridad, la cual, desde que finalizó el gobierno de Vicente Fox y la Fiscalía Especial para Movimientos Sociales y Políticos del Pasado (FEMOSPP) dio por terminados sus trabajos en 2006, fue abandona por periodistas, ya que los temas de la “justicia transicional” estaban pasando a segundo plano.

Los cambios consistieron en el retiro de la consulta abierta del fichero que hacía la función de guía, sin la cual, muchas de las peticiones de documentos comenzaron a ser negadas con el pretexto de su no existencia, y las que se aceptaban eran testadas en exceso.[1] No pasaron muchos días para que un grupo de investigadores[2] acordáramos realizar una carta[3] en la que planteamos tres preguntas al Secretario de Gobernación Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong (ya que el AGN es un organismo desconcentrado de la SEGOB) y a la directora general del AGN María de las Mercedes de Vega Armijo:

1.- ¿Por qué el archivo de la DFS sigue siendo administrado y custodiado por personal adscrito al Centro de Investigación y Seguridad Nacional (CISEN)?

2.- ¿Cuáles fueron las condiciones que obligaron a la aplicación de nuevos criterios de acceso? ¿Estos nuevos criterios fueron sancionados por el Consejo Nacional de Archivos?

3.- ¿Cuál fue la opinión emitida por el AGN, como entidad encargada no sólo de interpretar la normatividad en materia de archivos, sino de garantizar los mecanismos de acceso y consulta oportunos de la información, así como de promover la investigación de y en estos archivos?

Ciertamente el acceso y consulta nunca se cancelaron, pero la serie de candados impuestos por las autoridades del AGN significaban un cierre de facto. Aunque las autoridades de la SEGOB y del AGN no dieron una respuesta formal a las interrogantes planteadas en la carta entregada, la directora inició un proceso de “consulta informal” con investigadores y miembros de algunas instituciones educativas en las que se reafirmó el argumento legalista que gira alrededor de la categoría “archivo histórico confidencial.” La problemática permitió que se realizaran foros y se reabriera la discusión sobre el pasado reciente en México y los abusos del Estado, pareciera que buscando el silencio se provocó más ruido. Además de la carta, por medio de Facebook bajo el nombre de “Galería 1 Archivo y Memoria”. se ha ido construyendo una red de especialistas e interesados en el tema que ha permitido “darle tribuna” a encuentros y coloquios sobre la guerra sucia.

El 9 de junio de 2015, junto con el Instituto Nacional de Acceso a la Información, el AGN organizó un seminario cuyo tema central fue “El acceso a los archivos confidenciales históricos”, en dicho seminario fue unánime la condena de representantes de Article 19, National Security Archives, investigadores y miembros del senado[4] al argumento “legaloide” para impedir la consulta directa de los documentos.

El camino para lograr un acceso abierto e irrestricto a los fondos de la DFS parece aún largo, sin embargo es justo decir que no debemos desestimar los muy buenos esfuerzos de la investigación histórica basada en fuentes orales y las posibilidades que ofrece el acervo de la galería 2, en dónde se encuentra el archivo de la Dirección General de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociales, el otro brazo de la persecución política, cuya consulta es abierta e irrestricta. También será necesario hacer la debida crítica de fuentes sobre sus contenidos y la forma en que se obtuvo esa información, sin embargo en esos documentos se encuentra una estrategia de seguridad que de forma abierta buscó la eliminación de un grupo de mexicanos cuyas críticas al sistema político y económico los convirtieron en los acérrimos enemigos del gobierno. Permitir el cierre de la consulta del acervo de la Galería 1 del AGN implicaría mantener en calidad de desaparecidos a una buena parte de mexicanos y condenar a la democracia mexicana a un aspecto meramente procedimental y de fachada.

César E. Valdez es profesor investigador en la Dirección de Estudios Históricos del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. Es maestro en Historia Moderna y Contemporánea por el Instituto Mora y actualmente se encuentra realizando su investigación doctoral en El Colegio de México bajo el título de “Enemigos: vigilancia y persecución política en el México posrevolucionario 1923–1942”.

NOTES

[1] Camilo Vicente Ovalle resume en su texto “Los archivos de la represión o de la continuidad de la guerra sucia” que puede consultarse en línea aquí http://camilovicente.com/2015/04/13/los-archivos-de-la-represion-o-de-la-continuidad-de-la-guerra-sucia/ , la forma en que se realizaba la consulta hasta antes de enero de 2015. “Hasta el año pasado la consulta de documentos podía ser “directa” (mediando el criterio del personal del CISEN), y además solicitar versiones públicas, que eran testadas por el AGN. Sin embargo, a partir de enero decidieron aplicar un criterio (perverso según mi opinión) que se encuentra en el art. 27 de la Ley Federal de Archivos (emitida en el 2012) y que se refiere a que hay cierta información que, a pesar de ser histórica, su contenido sigue siendo delicado y por ello se les clasifica como “archivos históricos confidenciales”. Con esta clasificación, esos archivos quedan exentos de la Ley Federal de Transparencia, y la información puede ser reservada (eufemismo legal para ocultar y negar información) hasta por 70 años.”

[2] Entre los que se encuentran Camilo Vicente Ovalle, Rubén Ortiz, Mario Santiago, Carlos Inclán, Rodolfo Gamiño y quien esto escribe.

[3] La carta electrónica fue firmada por 1017 personas, de las cuales el 49% fueron estudiantes, un 17% se identificó como académico, el 16.5% como investigadores, un 1.4% como periodistas y un amplio 14.5% se anotó con ocupaciones varias que van desde profesores de educación media y media superior, gestores culturales, defensores de derechos humanos y artistas. La carta fue firmada por Barry Carr, Lorenzo Meyer, Sergio Aguayo Eugenia Allier, Robert Curley, Elisa Servín, Pablo Piccato, Alexander Aviña, Verónica Oikión, Pablo Pozzi, Gilberto López y Rivas, Andrew Paxman y un largo etcétera.

[4] En el seminario el senador Alejandro Encinas del Partido de la Revolución Democrática se comprometió a impulsar una Ley General de Archivos en la que se eliminaría dicho concepto, sin embargo, aún no hay una fecha en la agenda del senado para la discusión de la ley.

Commentary by Andrew Paxman

A Crisis of Leadership at Mexico’s National Archive

Restriction of access to Mexico’s secret police (DFS) files in January this year was a function of both state authoritarianism and weak leadership at the national archive (AGN). Despite a lifting of the de facto embargo in May, and despite subsequent talk of revising the 2012 Archives Law (a draconian reading of which produced the crisis), these traits remain worrying as they may recur in acts of censorship.

As I argued at the time—briefly at the news site Arena Pública and then at length in English—the government of Enrique Peña Nieto had set the tone for the clampdown through its assault on freedom of information in general. The trend reached a nadir with the March firing of tenacious radio host Carmen Aristegui, Mexico’s best-known investigative journalist. It is worth noting that the Peña Nieto regime has sought actively to shape and coopt the press, chiefly through generous ad buys that it can threaten to cancel should editors run critical stories. For more on this strategy, which dates from the middle years of the Felipe Calderón administration, see the recent reports by WAN-IFRA, Comprando complacencia (March 2014), and Article 19/Fundar, Libertad de expresión en venta (August 2015).

But if it was the state that set the aggressive precedent, AGN director Mercedes de Vega pulled the trigger, as she later admitted. She applied a 70–year embargo to the DFS collection (since the agency was founded in 1947, all of its records were covered), thereby forcing researchers to deal with a lengthy and uncertain waiver process. Whether or not De Vega was responding to a suggestion from the Interior Ministry, as some have surmised, is rather beside the point. Echoing earlier restrictive practices of De Vega’s as archive director at the Foreign Relations Ministry (SRE)—one researcher found her request for records on a World War II spy rejected on the grounds of a 70–year bar—the move affirmed what AGN insiders have decried as a tendency to place personal bureaucratic comfort over defense of research and scholarship.

That tendency is reflected in larger problems of AGN management. De Vega’s tenure as director was characterized from its August 2013 outset by high-handedness, markedly contrasting with the collegial style of her predecessor Aurora Gómez Galvarriato. Following the pattern of PRI bigwigs of the pre-2000 era, De Vega swept the AGN clean of key staffers, irrespective of their expertise and training, bringing in “her people.” A good deal of the institutional memory of the archive was therefore lost.

To her credit, De Vega has pursued the difficult project of a much-needed AGN annex, so to house its collections in a purpose-built environment. She has also been active in fostering the preservation of provincial and municipal collections, with Aguascalientes and Torreón among recent respective beneficiaries. The DFS incident, however, does not bode well for future occasions when an image-sensitive government seeks to block or restrict access to materials under the aegis of the AGN.

Andrew Paxman

Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE)

Commentary by Tanalís Padilla and Louise E. Walker

A few years ago, in an optimistic spirit, we edited a journal dossier entitled “Spy Reports: Content, Methodology and Historiography in Mexico’s Secret Police Archive” (Journal of Iberian and Latin American Research, 19:1, 2013). The archive, opened to the public in 2002 by presidential decree, consists of two collections: the intelligence reports gathered by the Dirección Federal de Seguridad (DFS) and the Dirección General de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociales (IPS). With this declassification, historians gained a fairly extensive and easy-to-consult primary source base for the second half of the twentieth century. The dossier brought together historians from the first generation of scholars who used the archive for original research, and its hybrid format combined traditional journal articles, published transcriptions of archival documents, and open-access English translations. With this project, we wanted to start a discussion about the new source and the politics and logistics of undertaking historical research on the decades after 1940.

In recent months our optimism has abated. Although the situation is still unclear, scholars and journalists have reported new limitations on consulting the DFS files. (See analysis by Andrew Paxman and Sergio Aguayo.) Because the DFS reports provide evidence of the state’s repressive policies from the 1960s to the 1980s, they play an important role in public debates about Mexico’s dirty war. Any fettering of access to the archive will impact the ability of human rights groups to investigate crimes, and the efforts of families of the disappeared to learn the fate of their loved ones.

There are also implications for scholars who study Mexico’s recent past. Depending on the nature of the access limitations—if any of the reported worst-case scenarios (such as a 70–year general embargo) become the new norm—the changes could stifle historical study of the post-1940 decades. The DFS files are a crucial source of information because so many other state institutions remain inaccessible. In our dossier we cited the examples of the Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP) and the Confederación Nacional de Organizaciones Populares (CNOP). In the case of the former, it is nearly impossible to consult documentation beyond the Cárdenas administration; the latter is just one example of the many missing (or unknown and unavailable to the public) archives for powerful state-affiliated organisations. Unlike the recent restrictions to the DFS, which seem political in nature, the historical documentation of other state institutions remains unavailable more likely due to a lack of incentives, priorities, and funding. But the logic of secrecy casts a wide net. The changes in the DFS archive do not bode well for future access to other collections that could help researchers understand and evaluate the nature and longevity of the PRI’s rule.

The secret police archive offered scholars privileged entry into the history of social and political movements, and in the subsequent 13 years a fledgling historiography emerged. As we conceived and developed the JILAR dossier, we discussed, with contributors and others, how to reckon with the first wave of scholarship. At the time, we anticipated continued access. We encouraged broad consideration of the advantages and disadvantages of this archive, and sought comparisons with works emerging from similar declassified collections in other parts of the world. While we were enthusiastic about the possibilities for research, we were—ironically it now seems—concerned that the archive might begin to loom too large and even distort the post-1940 historiography. We wondered what the historical scholarship would look like, in a decade’s time, if the majority of studies were based on research in the secret police archive. One possibility, which worried us, was that the paranoia, the mistakes, and deliberate manipulation of information that appear in the intelligence reports would infuse the scholarship. Such a historiography, in toto, could overstate dissent or reproduce the inaccuracies that plague the secret police files.

The new DFS restrictions have prompted a different set of questions and concerns about the archive and the historiography: Where should historians of the recent past look for primary sources? Will other collections, such as the IPS documents, suffer a similar fate? If the first generation of historians studying the decades after 1940 risked relying too heavily on the DFS collection, the handful of published studies might now become a historiographical anomaly. Continued use of the same archival collections, over several generations, is one way that scholars build robust historiographies. Creative and new approaches are sure to emerge, and indeed historians have worked in far more difficult circumstances, but the historiographical loss cannot be understated: researchers now have fewer avenues for the study of Mexico’s recent past.

Commentary by Kate Doyle

When President Vicente Fox decreed that Mexico’s “dirty war” files be opened for public access at the Archivo General de la Nación (AGN) in 2002, the decision was greeted by human rights advocates, journalists, scholars, and families of the disappeared as a welcome step toward transparency about a period normally shrouded by secrecy. It was the first time a Mexican president had acknowledged the government’s role in systematic human rights violations, and the first time any Latin American leader had unilaterally decreed that national security records about historical repression and state violence be made public to ordinary citizens. Fox’s move was especially surprising in a country typically controlled by its powerful elites through authoritarian rule, intolerance for dissent, and glacially incremental political change.

The handful of researchers interested in digging into the dirty war collection after its release approached it with a sense of excitement tempered by skepticism. Critics of the government had warned in press interviews that the collection was likely to be purged of any significant information. The fact was, we had no idea what we would find. A few scholars—most notably, Sergio Aguayo—had gained early access to a portion of the records following efforts to hold a truth commission. But there was no guarantee that the government had not cleaned the files of incriminating evidence before opening the collection, and besides, most of us didn’t know what Mexican government records even looked like. The freedom of information law was still a year away from implementation.

We dutifully applied for the researcher identification cards that would admit us to the AGN, and then chose a research room among the three “galerías” that contained the new dirty war files: Gallery 1 for intelligence records from the Federal Security Directorate (DFS), Gallery 2 for the archives of Political and Social Investigations (IPS), and Gallery 7 for the Defense Secretariat (SEDENA). Within hours of beginning, the value of the files was painfully clear. They encompassed millions of pages chronicling the sordid details of Mexico’s dark history—the government’s decades-long spying and disinformation campaigns, its covert infiltration of student groups, its coercion and bribery of the country’s intellectuals, journalists and opposition politicians. There were transcripts of interrogation sessions, counterinsurgency plans targeting entire communities in the mountains of Guerrero, photographs of tortured detainees and brutalized corpses.

The opening of the dirty war records was not without problems. Initially, there were no guides to the collections, making the identification of relevant records a puzzle. (You had to write down your research topic and then trust the archivist to locate the corresponding material inside the stored boxes, without recourse to an index or file numbers.) In Gallery 1 in particular—the intelligence records—the research room operated as the private fiefdom of a former DFS official, sent by the agency’s new incarnation, “CISEN,” to accompany the documents and control their release. The official used rules that only he understood to grant or withhold records, to favor or despise a researcher, without interference from the AGN or reference to any set of published regulations. Visiting researchers feared he was tracking them for intelligence purposes.

But obstacles aside, the dirty war records were and continue to be an invaluable trove that thousands of visitors have mined in the intervening years to produce new research about the past. It was also a critical source of information for the mostly disastrous “Special Prosecutor for Social and Political Crimes of the Past”—that was supposedly going to prosecute criminal cases around dirty war-era human rights abuses, but did none. One of the only valuable outcomes of that office was a flawed but groundbreaking 750-page report on the dirty war published in 2006 based on thousands of the formerly secret records. My own organization, the National Security Archive, used the collection to write the first investigation that identified the dead of Tlatelolco exclusively through evidence from the archives (as opposed to witness accounts).

Since the dirty war collection opened 13 years ago, there has been broad recognition across Latin America and around the world of the importance of open archives to understanding the past, providing reparations to victims, and achieving justice. Truth commissions have called on governments for the release of government archives to feed their investigations; more recently, prosecutors have used national security files in Guatemala, Peru, Argentina, and Uruguay to develop criminal human rights cases against aging perpetrators. As a result of the growing body of records documenting historical crimes of repression, human rights organizations have begun insisting that governments grant the “right to truth” about past atrocities. And an increasing number of access to information laws passed in the region include a clause prohibiting the withholding of information related to grave human rights abuses on any grounds.

For all these reasons and more, the Mexican dirty war archives are worth fighting for. Even though Mexico lags behind many nations in the hemisphere in pursuing judicial or even historical accountability, the records opened under the Fox administration will continue to serve as a vital source of evidence about Mexico’s repressive history.

Commentary by Sergio Aguayo (translation to English below)

Los archivos y la fortuna

Hay archivos afortunados. El acervo de la poderosa Dirección Federal de Seguridad (DFS) mexicana sobrevivió gracias a dos golpes de suerte. Actualmente se encuentra en el Archivo General de la Nación (AGN) donde enfrenta amenazas de diverso tipo.

La Dirección Federal de Seguridad fue la principal policía política de los gobiernos priistas. Fue creada en 1947 y terminó desbandada en 1985 cuando se hizo pública su degradación y corrupción. La mejor herencia que dejó el país es un registro excepcional sobre sus actividades.

Aurora Gómez Galvarriato (profesora de El Colegio de México) fue directora del AGN entre mayo de 2009 y septiembre de 2013. En su opinión, hay tres razones para su importancia: 1) pocos fondos documentales dan un panorama tan amplio sobre el régimen mexicano durante la segunda mitad del siglo XX; 2) hay un interés creciente entre los jóvenes historiadores por ese periodo; y 3) se preservaron integros. Esto último es notable porque el México autoritario hizo lo posible por borrar la evidencia de sus excesos y crímenes.

Su preservación se debe, en primer lugar, a que tuvo la suerte de contar con Vicente Capello y Rocha, el archivista de la DFS, que lo cuidó y lo defendió porque lo consideraba su creación. Capello tuvo éxito porque su caso es único. Sólo él entendía la lógica de los 60 a 80 millones de tarjetas (además de los expedientes y legajos respaldándolos) donde se resume lo que hicieron y dijeron los 3 a 4 millones de actores registrados. También había 26 mil videos y más de 250 mil fotografías.

El segundo golpe de suerte me involucra. A principios del año 2000 terminaba una historia sobre los servicios de inteligencia mexicanos. Solicité por escrito al Centro de Investigación y Seguridad Nacional (Cisen) autorización para consultar los archivos de la DFS que custodiaba. Me lo concedieron porque anticipaban la derrota del Partido Revolucionario Institucional en las elecciones presidenciales de aquel año; abrirme las puertas era una forma de apertura que permitiría certificar, de manera independiente, que el Cisen había acabado con las prácticas más nocivas de la DFS. Estuve trabajando más de un año en ese acervo y constaté su riqueza.

En julio del 2001 el Consejero de Seguridad Nacional, Adolfo Aguilar Zinser, arregló un encuentro personal con el presidente Vicente Fox a quien expliqué la trascendencia de depositarlo en el AGN. Fox instruyó a Aguilar Zinser que salvaguardara la documentación y meses después, el 19 de febrero de 2002, se hizo la entrega formal al AGN de 4223 cajas con los archivos de la DFS y la Dirección General de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociales.

En los trece años que han pasado desde entonces, centenares de investigadores mexicanos y extranjeron han consultado ese fondo documental cuya fortuna empezó a diluirse porque, en los primeros meses de este año, hubo un intento oficial de limitar el acceso. Los usuarios –actuales y pretéritos– lo interpretaron como una expresión de las políticas de opacidad del gobierno de Enrique Peña Nieto. Se organizaron para escribir cartas, organizar foros y reunirse con la actual Directora Mercedes de la Vega Armijo quien, abierta al diálogo, explicó que estaba atenazada por dos realidades: el marco legal y la falta de presupuesto.

Ambas realidades son resultado de una triste realidad: en el México que intenta ser democrático el conocimiento tiene una prioridad menor. El Congreso no se ha preocupado por crear leyes para proteger y garantizar el acceso a los archivos y dedica recursos escasos a los archivos. Es vergonzozo que el AGN tenga para el 2015 un presupuesto de 84 millones (cerca de cinco millones de dólares) para digitalizar, preservar y organizar fondos documentales enormes.

Por el momento el archivo de la DFS se mantiene abierto a la consulta aunque con las limitaciones atribuibles a la poca claridad de las leyes. Los gobiernos mexicanos presumen de la riqueza de nuestra historia pero hacen poco por preservar los materiales que permitirían entenderla mejor.

Los archivos de la DFS deben recibir el trato que se da a los acervos excepcionales. En este caso nos permite entender un pasado reciente y enfrentar los grandes problemas del presente. Por ejemplo, sostengo que en sus millones de hojas están algunas claves para entender el diluvio de muerte y sangre que nos ahoga.

La DFS utilizaba la violencia por razones políticas y conocía al detalle el mundo de la criminalidad; esas técnicas fueron transferido integras a la delincuencia organizada. Si entendemos por qué y cómo sucedió ese proceso podremos acercarnos mejor equipados al estudio de la racionalidad de los carteles que en algunas regiones de México han creado un estado paralelo. Ese es uno de los muchos tesoros que encierra el archivo de la DFS. No podemos, no debemos dejar su supervivencia en manos de la veleidosa fortuna.

Sergio Aguayo es Profesor de El Colegio de México. Profesor visitante de la Universidad de Harvard. Para esta investigación colaboró Anuar I. Ortega Galindo.

Archives and Fortune

There are fortunate archives. The collection of the powerful Mexican Dirección Federal de Seguridad (DFS) survived thanks to two strokes of good luck. It currently is located in the Archivo General de la Nación (AGN), where it has faced various types of threats.

The Dirección Federal de Seguridad was the frontline political police force for the PRIista governments. It was created in 1947 and finally disbanded in 1985, when its depravity and corruption became public. Its greatest legacy to the country is an exceptional record of its activities.

Aurora Gómez Galvarriato (a professor at El Colegio de México) was director of the AGN from May 2009 until September 2013. In her opinion, there are three reasons for the collection’s importance: 1) few documentary collections offer such a broad panorama of the Mexican regime during the second half of the twentieth century; 2) there is a growing interest in this period among young historians; and 3) it is preserved intact. This last point is notable, because authoritarian Mexico did everything possible to erase the evidence of its crimes and excesses.

The collection’s preservation is due, first and foremost, to the luck of having as DFS archivist Vicente Capello y Rocha, who cared for and defended it because he considered it his creation. Capello succeeded because he was in a unique position. Only he understood the logic of the 60–80 million cards (in addition to the files and dossiers holding them), which summarize what some 3 to 4 million registered actors did and said. There were also 26,000 videos and more than 250,000 photographs.

The second stroke of good luck involved me. At the beginning of 2000, I was completing a history of the Mexican intelligence services. I submitted a written request to the Centro de Investigación y Seguridad Nacional (CISEN) for authorization to consult the DFS archives in its custody. They granted me access because they anticipated the downfall of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) in that year’s presidential elections; opening the doors to me was an opening that would permit independent certification that CISEN had terminated the DFS’s most harmful practices. I worked for over a year in this collection and confirmed its richness.

In July 2001, the national security adviser, Adolfo Aguilar Zinser, arranged for me a personal meeting with President Vicente Fox, to whom I explained the importance of depositing the collection in the AGN. Fox instructed Aguilar Zinser to safeguard the documentation, and months later, on February 19, 2002, 4,223 boxes from the archives of the DFS and the Dirección General de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociales were formally delivered to the AGN.

In the 13 years that have passed since then, hundreds of Mexican and foreign researchers have consulted this documentary resource, whose good fortune began to diminish in the first months of this year after an official attempt to limit access to it. Users—current and previous—interpreted the move as an expression of the Peña Nieto government’s politics of obfuscation. They organized themselves and wrote letters, held forums, and met with current director Mercedes de Vega Armijo, who, open to dialogue, explained that she was constrained by two realities: the legal framework and the lack of funds.

Both realities result from a sad truth: in a Mexico that is trying to be democratic, knowledge has a lower priority. Congress is not concerned about passing laws to protect and guarantee archival access and dedicates paltry resources to the archives. It is shameful that for 2015 the AGN has a budget of only 84 million pesos (approximately 5 million US dollars) to digitize, preserve, and organize enormous documentary collections.

For now, the DFS archive remains open to consultation, albeit with limitations attributable to the laws’ lack of clarity. Mexican governments boast of our rich history but do little to preserve the materials that would allow us to understand it better.

The DFS archive deserves to be treated as all exceptional archives are. In this particular case, it allows us to understand the recent past and to confront the major problems of the present. For example, I maintain that in its millions of pages there are some clues to understanding the deluge of blood and death in which we are now drowning.

The DFS used violence for political reasons and knew the criminal world in detail; these techniques were transferred intact to organized crime. If we understand why and how this process unfolded, we can be better equipped to study the rationality of the cartels that in some regions of Mexico have created a parallel state. That is one of the many treasures contained in the DFS archive. We cannot—we must not—leave its survival to the vagaries of fortune.

Sergio Aguayo is Professor at El Colegio de México and Visiting Professor at Harvard University. This research is a collaboration with Anuar I. Ortega Galindo.

Gracias Sergio por tu siempre atinado comentario

GerardoFco Vierling Hdez

Estimados colegas:

Los invitamos a conocer, sumarse y difundir la petición para que sean eliminadas las restricciones a la consulta del fondo de la Dirección Federal de Seguridad en el Archivo General de la Nación-México. Después de meses de denuncias, promesas incumplidas y negación de lo que está ocurriendo en torno a la consulta de dicho fondo, hay que seguir dando la batalla contra esta situación que no sólo dificulta la investigación histórica y el acceso a la justicia, sino que sienta un precedente en materia de acceso a la información pública gubernamental, lo que a todos debe preocuparnos por la cantidad de crímenes que se están cometiendo en la actualidad.

Aquí la página de la causa donde pueden sumarse al Pronunciamiento contra las restricciones a la consulta del fondo DFS en el AGN

https://www.change.org/p/pronunciamiento-contra-las-restricciones-a-la-consulta-del-fondo-dfs-en-el-agn?recruiter=61575913&utm_source=share_petition&utm_medium=copylink

Ésta es una iniciativa del Seminario Nacional de Movimientos Estudiantiles al cual pertenecen académicos y estudiantes de diversas instituciones de educación superior mexicanas y que abrimos a todo aquel que desee sumarse, firmar y difundir.