A Camera in The Garden of Eden. Questions to Kevin Coleman

As I read this book, I was surprised by Kevin Coleman’s command over multiple lines of inquiry. The book develops a new way of thinking about issues that the historiography of Latin America has long been concerned with, and that Coleman is consolidating in several initiatives (http://kevincoleman.org/). The questions that I posed to him revolve around his experience with the archives, especially photographs. As this interview indicates, the book is part of an intense reflection on a cluster of issues that should not be separated.

Nicolás Quiroga [NQ]: What led you to do research on Latin America, and Honduras in particular? What led you to write this book?

Kevin Coleman [KC]: After finishing an undergraduate degree in philosophy, I served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in southern Honduras (1997-1999). The decision to represent, even in some low-level way, the U.S. government in Central America was not one that I took lightly. But I felt that even though the United States had violently undermined social movements that sought a measure of economic and political equality, I could still accompany Hondurans who continued to struggle for these goals. I dedicated myself to learning from campesinos who organized to protect their local watersheds and to bring potable water to their communities. In my early twenties and living in Texiguat, El Paraíso, I used to ask my friends why Hondurans hadn’t rebelled against the United States when the rest of the region did, and why so few knew that the U.S. had toppled democratically elected governments in Central America. Some years later, I decided that the best way for me, as a U.S. citizen implicated in the plight of Hondurans, to seek some sort of justice would be to investigate how the unequal relations that reign today were made by historical subjects. These issues of U.S.-Latin American encounters dramatically come together in struggles around the production of bananas for export on the North Coast.

But I didn’t actually start out doing research on the banana companies or the visual. I intended to study the campesino movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and the U.S.-backed political violence of the 1980s. Laid off after the 1954 strike and massive flooding of the plantations, unemployed banana workers were suddenly rendered landless peasants. These former wage laborers led the struggle for agrarian reform in Honduras. So I went to El Progreso because the town had been the epicenter of both the labor movement of the 1950s and the campesino movement of subsequent decades. The more I researched the late-Cold War agrarian struggles, the more I realized that the foundations for these conflicts were laid between 1880-1954.

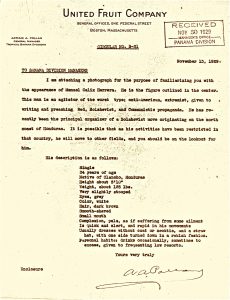

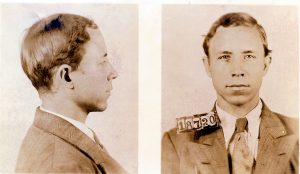

Dated November 15, 1929, this internal United Fruit Company memorandum on Manuel Cálix Herrera was circulated, with two identifying pictures attached, to division managers. Courtesy of United Fruit Company Letters, Bocas del Toro Division.

NQ: Your book moves between different scales and temporalities. It’s about a small town in Honduras and about the United Fruit Company; it’s about a photographer but also about Central American workers who famously went on strike in 1954; it’s about the history of a country but also about colonial imagination; it’s about “facts” and the archive but also about ways to contextualize the lives of historical subjects and the historiography that attempts to understand them. Yet it is the life of the photographer Rafael Platero Paz and of the people of El Progreso that he photographed that serve as the foundation for the themes explored in this book. What does the idea of “self-forging,” central to your study, add to our understanding of modernities in Latin America?

KC: Indeed, the book is structured around a tension between the efforts of people in El Progreso to shape their own lives and the neocolonial power of the United Fruit Company. I attempt to keep this tension in play at every level, especially when examining the role of photography and visual culture in the imperial encounters between workers and the company. Photography has long been used to discipline people and rationalize nature. These two ways to maximize production come together in a photograph that the United Fruit Company used to guard against the influence of labor leader Manuel Cálix Herrera. But the camera has also been used for self-representation (selfies are not a recent invention!). In a broadly accessible way that portrait painting never achieved, photography enabled ordinary people to picture themselves as they wished to be seen by others.

When I speak of self-forging, I’m signaling the ways that individuals collaborated with a photographer to make pictures and, just as importantly, the ways that groups of people made themselves with others. The photograph of the line of striking banana workers serves as the perfect allegory for what I’m trying to show in this book. Those closest to the camera are rendered as individuals, but as the line recedes, the workers appear as a single collective subject. They are making themselves with others —with the photographer, with the United Fruit Company, with local merchants, and with their national government in Tegucigalpa.

Photography, that quintessential emblem of modernity, offers us both an indexical, mechanical trace of selected moments in which light bounced off of a subject in front of a camera and an artist’s framing of a particular image. In a fundamental way, every photograph is connected to the moment in which it was made. That makes it a unique kind of historical document.

NQ: What are the particularities of the photograph as a document?

KC: Photos are not unproblematic records of encounters between people, a photographer, a camera, and viewers. Instead, they are always inexhaustible, and the event they record is never finished. The very existence of the photograph enables some potential spectator in the future to reopen it, to reinterpret it, as Ariella Azoulay has argued.

I like to think of photographs as both evidence of a slice of time and an artistic rendering of it. Since the nineteenth century, efforts to claim that the photo is one but not the other—that is, an index of something in the world but not artistry, or vice versa—have always crashed up against the rocks. Even today’s most abstract fine art photography constantly seeks to exploit this tension. None of us has the final word on the meaning of a photograph. The camera always records more than the photographer and her subject intend (this is what Walter Benjamin called the “optical unconscious” and what Roland Barthes celebrated as the “punctum”). But despite the photographer’s lack of full control over the image, the act of framing one thing rather than another is not inconsequential. The choice of what to photograph, and how to photograph it, is significant.

This is what makes Rafael Platero Paz so interesting as a character. He photographed himself and others. He photographed thousands of working people who couldn’t read and write, and who entered the historical archive, if at all, primarily through their interactions with the state (birth, death, and maybe a criminal record). But in his photographs, these folks collaborated with Platero Paz to get a picture of themselves. Photography enabled a kind of self-authorship that was otherwise unavailable to the plantation laborers who produced bananas for consumers in the United States, Canada, and Europe. And it wasn’t just through studio portraits that workers represented themselves. When humble men and women staged the sixty-nine day strike in 1954, they quite literally changed what could be seen, said, and done in the banana plantations of northern Honduras. Before the strike, thousands of workers could not sit outside the exclusive American Zone; they couldn’t occupy the Ramón Rosa Plaza in El Progreso; they couldn’t get their local Jesuit priests to say outdoor masses just for them; they couldn’t go to their own collectively run health clinics or communal kitchens. In staging the strike, they restructured their world. The company and the Honduran state had to recognize them as workers and as citizens, the dual registers through which they made their demands.

NQ: Reading your book reminded me of many terms that are applied to photography or related to it (phantasmagoria, “seen and unseen,” among others). It’s easy to argue that images have multiple meanings, but what distinguishes A Camera in the Garden of Eden… is that the book is always interrogating that emptiness, and examining what remains outside and beyond the indexically given. Bearing in mind the many dimensions of photographs (temporality, spatiality, horizons of expectations…) your gaze is converted into a method of interpretation that can be learned by the reader. What did you do to forge that gaze? What sort of basic program might one consider to interpret images?

KC: I like the way you put the question—“está interrogando sobre el vacío, sobre lo que queda fuera de lo indizado. ” Rather than simply restraining myself to an account of the past, I foregrounded my methods of inquiry—explicitly stating how I was reading images, archives, and public performances—so that other scholars could adopt, modify, or reject these methods.

What happened in the past, and how we got from there to the present, was really only one of my concerns in this project. I was also interested in how we know what happened and in how new source material might not only generate new facts but also new ways of thinking about the past and the present. Both of these issues were linked to a certain ethical obligation as a U.S. citizen, aware of the degree to which the wealth of my country had been extracted in part from Central American workers and soils that were systematically, sometimes violently, cheapened. So I sought to braid four domains of inquiry—historical, epistemic, ethical, and aesthetic. I wanted the book to be historical and meta-historical, to be about the past but also about forging new relationships to the past, as knowers, as students, as viewers of pictures, and as members of different political communities. I want the book to prompt some sort of affective engagement with the past, and to leave readers with enough space to respond to some of the images on their own.

To do this, I had to learn how to treat images as images. Early on, I saw that our colleagues in art history and visual culture studies had contempt for the ways that historians have worked with photographs. I knew that they were right. The first generation of historians to use photographs as source material often treated images as unproblematic sources of information. But that doesn’t work. Photos are indexes of moments when light bounced off an object and changed photo-sensitive material in the back of a black box. But the meanings of those images aren’t fixed. They aren’t held in place. Any photograph can always be reinterpreted.

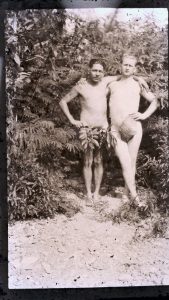

Nevertheless, interpretive indeterminacy is not the same as interpretive impossibility. This is an idea explored throughout the book, but especially as I try to think about the meanings of a homoerotic photo of Rafael Platero Paz posing unclothed with a white man as both cover their genitals with leaves. Photographs do enable us to say some things with a fair degree of confidence. The two men were obviously, and playfully, citing the ancient story of the Garden of Eden. My strategy with that image was to put forward a number of plausible interpretations of it, and then to point out why they didn’t hold up (e.g., that the white man had coerced the brown one into posing naked together). I used signs encoded within the image and the technical choices of composition and exposure to argue that this was not another picture of racial hierarchy. From there, I attempted to argue that this photo, which in some circles would still be considered scandalous, was of a moment, however brief, of radical equality in a highly unequal space. I understand this photograph as an allegory for Platero Paz’s entire archive as one of contact, over and against the United Fruit Company archive of separation and classification.

The Garden of Eden. Courtesy of the Rafael Platero Paz Archive.

NQ: That photograph, reproduced in your book, seems to have challenged you….

KC: So if a historian wants to work with visual sources, the first thing to do is look at the pictures. Photographs, like textual sources, need to be interpreted. Neither offers up unmediated insights. Looking at a picture involves describing what’s in the frame, and this description is an initial act of interpretation. But a photograph is only a site to begin thinking about what must have been going on outside of the frame. That is, the photo serves as a sort of portal for imagining a particular moment captured on film. The task of the historian, or the spectator, is to embed that image in its context. How was the image created? How was it subsequently used? Where did it circulate? Did different contexts of exchange resignify the image, unmooring it from previous meanings it may have taken on? This is where historical methods are joined to the methods of art history and the conceptual tools developed by theorists of visual culture. Traditional historical archives—newspapers, court documents, company memoranda, diaries, expense accounts—are the bedrock upon which interpretations of the visual record are built. But once a photograph is grounded in the context from which it emerged, the historian must return to the image itself, to the photographer’s decision to frame one bit of the world and separate it out from the rest. That act of framing by the person behind the camera is significant and requires interpretation. Likewise, the poses and appearances of what is captured within the frame are significant. The historian has to be open to engaging with the image-object. An image sets in motion what Kant called “the free play of the imagination.” Archives of photographs demand, indeed enable, an ethics of engaged historical imagination.

NQ: In your book, you are examining the Logic(s) of Capital. The idea is that, in neocolonial spaces, workers have to convert themselves into visual subjects before they can become political subjects, which I understand as one of the central arguments of the book, one that permits you to narrate anew a history of the 1954 strike. In reading this chapter, I realized that the photographs do not illustrate a narrative that we already knew, that they don’t confirm what we already know, rather that they are interpreted to think through the process in another way. But in addition to teaching us the risks of treating images as reflections of reality, the chapter demonstrates the power of Mirzoeff’s notion of “countervisuality.” How did you go about interpreting the 1954 strike in light of these two archives, that of Platero Paz and of Life magazine (considered in a different chapter)?

KC: You’re right: the 1954 strike is a defining moment in twentieth-century Central America, a massive event, in the full sense of the word. We have a sophisticated historiography of the strike: from Darío Euraque’s examination of the ethnic differences that led to the development of a distinctively liberal political culture on the North Coast, to Marvin Barahona’s invaluable oral histories, from John Soluri’s pathbreaking environmental history of the United Fruit Company, to Suyapa Portillo Villeda’s study of the role of gender among campeños and campeñas. The broader historiography of the company is also well-developed, with landmark studies on race and ethnicity by Aviva Chomsky and Philippe Bourgois, as well as Lara Putnam’s work on gender and West Indian migration and Steve Striffler’s analysis of peasant-worker activism in Ecuador. This is the incredible historiographical backdrop against which I was writing.

I tried to argue that photographs allowed banana plantation workers, peasants, and women to represent themselves as full citizens long before the company or the state accorded them any such status. In making this argument, I had to break with the existing scholarship on political culture and nation-state formation in Latin America to examine two ideas. First, I attempted to show that certain social and legal devices of political exclusion were inherently visual, as were many of the countervailing popular claims to citizenship. For example, a newspaper photo of workers who had been beaten for attempting to organize a labor union graphically denounced an injustice while also calling upon those who saw the image to help restore the people’s right to freedom of association, which had been suspended by the government. Second, I wanted to demonstrate the ways that photographs captured and constituted processes of cross-class identity construction. When photos weren’t being used to denounce an injustice or to make avowedly political claims, members of all social groups tended to adopt a middlebrow aesthetic. Workers and merchants, peasants and fruit company managers: all posed in their best clothes to have pictures taken that would subsequently be hung on living room walls or, in the case of Palestinian immigrants who made their living as merchants in El Progreso, be sent as postcards to family back home in Jerusalem. By tracing the outlines of popular photographic practices that went beyond the nation and couldn’t be controlled by the state, I found that the transnational circulation of photographs impinged on ideas of national membership to create broader categories of belonging and claims to the protections that full citizenship should afford.

NQ: The scene of the strike, when seen through photographs becomes denser….

KC: So my reworking of the strike as interior exercises in individual and collective self-government emerged less from the existing historiography on the strike, and more from interpreting what remained unremembered yet clearly encoded within the photographs that Platero Paz took in El Progreso, the epicenter of the Honduran labor movement. With his photos in front of me, I began reading traditional sources to track changing conditions of visibility: to see how people altered who could be seen doing what when and where, as well as the ways that the company marked off its (private) spaces and restored order by using (public) security forces. The popular religiosity that animated the workers, their prayers, and the outdoor Masses: these themes are absent from the secondary literature on the defining event in twentieth-century Honduras. Platero Paz’s pictures enabled me to recover gazes, as well as embodied practices, that would otherwise have been obscured by the myth of progress in El Progreso. But the visual artifacts, and the ways that workers changed the ways that public and private spaces could be used during the strike, do not speak for themselves. I interpreted these visual artifacts within the context of the material and social structures of early Cold War Central America. I sought to create narrative and analytical links while also taking stock of the technical constraints of the camera as a mechanical device, and, crucially, by making judgments about what we can infer regarding the intentions of the photographer and his subjects as they produced specific moments on film.

Through photographs, workers made their struggle visible to outsiders. Life magazine could have provided its audience with the visual means for establishing affective ties to civic actors in Honduras; but it hid those images away, publishing only one dramatic full-page image of the striking banana workers. In contrast, Bohemia of Cuba published twenty-four pictures of the sixty-nine day strike, using the photographic image to document and extend the workers’ performance of their embodied citizenship. In staging the strike against two powerful U.S.-based fruit companies, the workers created images of themselves as laborers and as citizens. By 1959, Honduras enacted a series of labor protections, enshrining the collective will of the banana workers into new rights. Photojournalistic images played a part in labor’s successful struggle for recognition.

Rafael Platero Paz made many photographs of the striking workers standing in orderly lines. Courtesy of the Rafael Platero Paz Archive.

NQ: It’s incredible how the line of workers (an important photo for your book, and the one that is on the cover) or the one of the workers on top of the train are extended expressive forms of the history of Latin American labor (and perhaps that of other places as well), and at the same time, they are such tangible testimony of what they attempt to show. Your book is an effort to formulate new ideas on the transnational but also I believe it implies a rethinking of the local. Beyond fashionable notions of “complexity” or the “dialectical” in this duo, your book crosses this binary with that of the past/present through visual archives, making the conversation more impassioned and difficult. In writing this book, what did you learn about these interconnections, ones that prove fundamental to the historiography of Latin America?

KC: Photography lends itself to both the oscillations that you mention, the movement between the transnational and the local, and between past and present. From John Soluri’s agroecological study, I learned that to understand the banana plantations, you have to link the production of the fruit in Latin America to its marketing and consumption in North America. The United Fruit Company produced images on a massive scale. At the same time, many poor Hondurans had indirect access to the means of image production. Across the North Coast, fotógrafos de cubeta would walk through banana camps taking pictures for one Lempira, enabling poor workers and their families to obtain mementos of themselves in their Sunday best. So I start by following the commodity chain, only to find the ways in which it is disrupted by images of workers producing themselves as citizens worthy of certain protections.

At each stage, I’m concerned with questions of sovereignty. Who got to decide how things were done in El Progreso? How were these decisions negotiated? There were certainly examples of a Schmittian sovereign, including when the United States brokered a military agreement with Honduras during the 1954 strike (just as the CIA was preparing the overthrow of the democratic government of Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala). But the 1954 strike offers an example of popular sovereignty, of women and men coming together to govern themselves, individually and collectively. Photographs of the striking workers document and extend these moments for potential spectators in other places and times. They keep open futures that the company and the U.S. and Honduran governments sought to foreclose. In imaginatively entering the spacetime in which a photograph of the strike was made, I attempted to retrieve something of the aspirations of the people who risked so much in demanding higher wages, better treatment, and a few basic liberal democratic rights.

So it’s the temporality of the photograph, I argue, that invites us to radically historicize. But my book isn’t another celebration of photographic realism, or of the photograph as evidence. Instead, I create a hermeneutic circle that seeks to continually examine how photographs can be used to generate an analytical narrative of the past. That’s why the archives are characters, collective ones at that, in this story. Pictures are agential objects, as are the archives from which they come. Images act on us, even as we act on them. And at the very least, every photograph is a document of an encounter between a photographer, a camera, and a photographed subject. This is the “that-has-been” of photography, a temporality that indicates to the viewer in her present that she is seeing a fraction of a second from the past. It is our duty as spectators to think through what the photographer framed, and to think outside of the frame—that’s the tremendous methodological implication of Ariella Azoulay’s notion of “the event of photography.”

But when the concepts of other scholars didn’t help me make sense of my source material, I had to theorize other ways of working with these images. For example, in thinking through a failed photographic encounter, I realized that the subaltern’s absence from the archive might be the exact point at which he most fully exercised a choice not to be pictured by others. In a short article, I ended up calling this “the right not to be looked at,” an idea that seeks to qualify recent theorizations of “the civil contract of photography” by Azoulay and “the right to look,” by Nicholas Mirzoeff. Essentially, I argued that when Life magazine’s Margaret Bourke White tried to photograph a dying old man in the mountains of Honduras, this peasant asserted his right to be left alone. As we face a barrage of electronic intrusions into our lives, we need to bear in mind the right to privacy, the right not to be entered into the visual record. So even as we attempt to imagine ways that photography can enable us to be together across borders in practices that the neither nation-states nor capital can fully control, we must still defend everyone’s right not to have their life archived by others, by a state or a transnational corporation.

NQ: What are you researching now?

KC: I’ve just started a project on photographs of Archbishop Romero in El Salvador. This is requiring me to think through questions of iconoclasm, idolatry, and different theologies of the image. The key actors, from the Salvadoran military to lay Catholics, treated images as if they were more than representations.