Latin America and the World Cup: An Interview with Joshua Nadel

1. What historically accounts for soccer’s popularity in Latin America?

Soccer arrived in the region just as modern nation-states were beginning to consolidate in the late 1800s. Massive waves of immigration began to alter many of the societies, while the end of slavery broadened the polity in others. At the same time, export-led growth and the development of national infrastructure altered people’s outlook. The sport got to the region at this moment, as a part of the neocolonial landscape. It was brought by the English (and Scottish), paragons of civilization. As a result, the sport, as played by men, became associated with notions of progress, modernity, and nation. So soccer tied into the way that nations and people saw themselves, acting as both a reflection of and an idealized projection of what people wanted the nation to be. To some extent, the sport continues to perform this role.

It’s important to note that women played soccer in the region starting in the early twentieth century (maybe earlier), but their activity was seen as transgressive and threatening. While women fandom was acceptable, women playing in soccer was not.

2. What is the significance of the World Cup for Latin American nations?

The men’s World Cup is one place where Latin American nations, still beholden economically (and to a degree culturally) to Europe, can compete and beat politically more powerful and more developed nations. Winning the men’s World Cup, or defeating a rival nation in it (either from within or outside the region), offers a symbolic victory to the nation on a level playing field and allows the nation to highlight their ability. For example, in 1924, when Uruguay won the Olympic soccer competition (which is considered the first men’s world championship by FIFA), it was seen as a triumph of the Uruguayan nation as a whole. It literally, paraphrasing one journalist at the time, put the country on the map (the Uruguayan flag was flown upside down at the opening ceremony). So there’s a psychological aspect to the men’s World Cup that plays into national pride. At the same time, let’s not forget that there’s a practical side too. During the month of the tournament, when the national team plays, people don’t go to work. Kids don’t go to school.

3. In your book on soccer in Latin America, you carefully trace how national teams help to mediate differences internal to a country and create a unified sense of national identity. How does this dynamic hold for this year’s World Cup, when the tournament coincides with contentious elections in Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia?

While soccer can help unify nations, I think that the idea can be taken too far. For example, in 1978 the World Cup didn’t really unify Argentina—it gave the military dictatorship the veneer of international legitimacy that covered over its continued persecution and murder of political opponents. That said, armed groups did call a ceasefire for the duration of the tournament. It’s also important to distinguish between helping to unify a national identity and helping to create common ground politically. I don’t think that soccer is particularly well suited for the latter. Soccer may transcend politics in that everyone can back the selección/seleção or that people from across the spectrum can support a particular team, but it doesn’t bridge divides between political ideologies. In fact, soccer is used by all parties on the political spectrum to mobilize support for their viewpoints.

As far as elections go, in other words, I don’t think soccer, even the national team, is particularly unifying. It may—as Brenda Elsey pointed out in Citizens and Sportsmen—act as a training ground for political practices such as campaigns and voting, as well as for politicians themselves. She notes that many politicians from the working class got their start in union-based or community-based soccer teams. This happened elsewhere in the region too. Soccer also offered politicians patronage opportunities. In the past, stadium construction was seen as a way to build support for a government, while in some cases politicians offered houses and/or jobs to national team members for good performance. As a senator, for example, Salvador Allende suggested that the 1962 Chilean men’s World Cup team be given houses.

I don’t think that the men’s World Cup played a large role. There was some talk in 2014 that a Brazil victory would help Dilma Rousseff’s reelection bid, but Brazil was the tournament host, which gives the discussion a slightly different flavor. Some studies show that incumbents can get a 1-2 percent bounce with major victories, but only within days of the victory. So even if Brazil were to win, it likely wouldn’t affect the election in October. There was some posturing in Colombia—Ivan Duque appeared in a Colombian jersey on fake Panini stickers and Gustavo Petro showed up to the polls with his daughter in a national team shirt—but those are little more than gimmicks. As for Mexico, while the election campaign was contentious, Lopez Obrador’s margin of victory was too large for any World Cup effect to matter.

4. You’ve discussed the idea of the importance of national teams playing up to a putative “national style”; indeed, in your book you recount an anecdote of Argentine fans reacting better to a loss than a win because the former was played with “la nuestra.” Can you explain a bit more the origins of this idea of national style, and how are the Latin American teams faring in this year’s World Cup according to that metric?

The origins of national styles stem from the desire on the part of organic elites—be they politicians, journalists, and others—to forge some sense of national unity. This ties back to the timing of the arrival and popularization of soccer in the region. In the case of Argentina, journalists in the magazine El Gráfico (and others as well) began crafting the idea of the Argentine style as a way to distinguish Argentine soccer—and thus the Argentine nation and the Argentine people—from their neighbors and from their European opponents. The basis of Argentine style was the pibe—a young boy (and it was always a boy)—who dribbled the ball the same way that he maneuvered through life’s hardships; poverty, hunger, whatever. The construction of the pibe as a national type coincided with the widening of suffrage in the second decade of the twentieth century and the renovation of folklore and the gaucho, that Oscar Chamosa has written so eloquently about, in the early 1920s. It came at a moment when Argentina was looking to alternatives to Europe for models of society and culture, and at the same time that it was working out how to deal with turning immigrants into citizens.

The same can be said for Brazil, though the Brazilian discussion on national style starts a little later, in the 1930s. Here, instead of immigrants, the development of national style helped to incorporate, at least rhetorically, the Afro-Brazilian population. Gilberto Freyre opened the discussion of futebol mulato when he was in France to cover the 1938 men’s World Cup. Freyre’s writing was followed by Mario Filho, who wrote O Negro no Futebol Brasileiro, in 1947. These two, along with others, really suggested that there was a Brazilian style based on the rhythm and playfulness of the Afro-Brazilian population. These ideas resonated with Getúlio Vargas, who foregrounded this style of soccer (the jogo bonito—a term coined by the Brazilian journalist Tómas Mazzoni), capoeira, and samba as important Afro-Brazilian contributions to Brazilian society.

In reality these national styles also played on nineteenth-century ideas of scientific racism. Innate soccer traits hewed pretty closely to ideas about race more generally. Europeans were logical and level-headed, Latin Americans improvised everything and played with more passion, Latin Americans of African descent played as though they were dancing. And I’d also be remiss not to mention again that the use of soccer as a way to define the nation was a strictly masculine affair. That is, men playing the game helped to define the nation, for men. Women’s soccer was actively suppressed in much of the region (the Vargas government banned the sport in 1941 and the ban remained in place until 1981). While women continued to play the sport, they were criticized and ridiculed for doing so.

As far as how the teams are doing based on these supposed styles, Argentina surely failed to play well and to play “la Nuestra.” It’s been a long time since the Argentine team played this way, if it ever really did. Brazil, I think, is living up to some of the hype. The opening game draw notwithstanding, there have been flashes of futebol arte in the tournament. And Uruguay, which is known for playing with garra Charrúa, has probably done the most to live up to the hard-nosed, perhaps overly physical style that is associated with the nation.

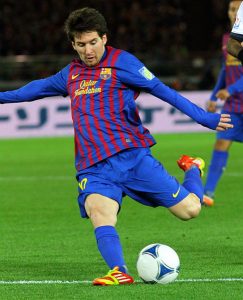

5. This is set to be the last World Cup for the legendary Argentine star Lionel Messi. How are that country’s fans reacting to this last run, and is there a particular historical context for this reaction? (On a somewhat related note, why is Messi known as “la pulga” [the flea]?)

The nickname is because he is small and quick. As far as Argentine fans. . . . He’s a bit of a lightning rod in Argentina. He faces incredible amounts of criticism when the team loses—and even sometimes when they win. He is often (incorrectly) assumed to be aloof and unconcerned about national team performances. Much of the reason for this is that he left Argentina for Barcelona at age 13, and part of it is because Messi is always compared to Maradona. Maradona always wore his heart on his sleeve. He appeared to be trying hard even when he wasn’t, and he played the first six years of his career (and the final four) in Argentina. Where Maradona lived in neon, Messi shies away from the spotlight. Where Maradona was demonstrative, Messi prefers to lead quietly. In fact, much was made of the way he visibly took over leadership of the team during the Nigeria game. But Maradona has always been incredibly supportive of Messi, suggesting—as others do—that he can’t be expected to singlehandedly bring the team a championship.

But many fans in Argentina have reacted the way they often do: with a healthy dose of amnesia. Messi led Argentina to two straight Copa America finals and one World Cup final, in the space of three years. That they did not win one shouldn’t diminish Messi in anyone’s eyes, but it does. Some have criticized him for returning directly to Barcelona after Argentina’s elimination from the 2018 men’s World Cup, instead of going to Buenos Aires. At the same time, as far as I know, Messi is the only player to have a special section of a newspaper devoted to him, as Olé (Argentina’s biggest sports paper) does. And as far as they’re concerned, he might not have played his final World Cup. A recent article pointed out all of the players over 30 who have played important roles for their countries at the men’s World Cup.

6. What further reading would you recommend to someone interested in learning more about soccer and the World Cup in Latin America?

Brenda Elsey’s Citizens and Sportsmen is my favorite book on soccer in Latin America. It’s at once a great social history of soccer and of the formation of social class and working-class citizenship. Julio Frydenberg’s Historia social del fútbol: Del amateurismo al profesionalismo is another that traces the social history of soccer. A lot came out around the 2014 World Cup, much of which focused on Brazil. Roger Kittleson’s The Country of Football and Bernardo Buarque de Hollanda and Paolo Fontes’s edited volume by the same name are both important and worth checking out. Gregg Bocketti’s book on soccer and modern Brazil is also a really good read. Pablo Alabarces has a number of great books and articles on Argentine soccer, and his work with Maria Graciela Rodríguez really stands out. What I’ve been reading most about lately is women’s soccer, and there are a lot of great articles but very few books. Among the authors to check out regarding women’s soccer are: Silvana Vilodre Goellner on Brazil, Adolfina Jansen on Argentina, Luz Elena Gallo Cadavid on Colombia, Fausta Gantús and Martha Santillán Esqueda on Mexico, and Esther Lopez-Portillo. For something outside Latin America, Laurent Dubois’s Soccer Empire is phenomenal. I haven’t had a chance to read his Language of the Game yet (hard to get where I live), but I look forward to it on my return.

Joshua Nadel is an associate professor of history at North Carolina Central University in Durham, North Carolina. He is author of Fútbol!: Why Soccer Matters in Latin America (University Press of Florida, 2014) and co-author (with Brenda Elsey) of Futbolera: A History of Women and Sports in Latin America (forthcoming, University of Texas Press). He has also been curating a playlist for the men’s World Cup on Tropics of Meta, a blog edited by (among others) Alex Cummings and Romeo Guzmán.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.