Interview with Lillian Guerra, author of “Poder Negro in Revolutionary Cuba: Black Consciousness, Communism, and the Challenge of Solidarity”

Lillian Guerra is professor of Cuban and Caribbean history at the University of Florida. She is the author of a book of Puerto Rican history, published in 1998, and three books of Cuban history: The Myth of José Martí: Conflicting Nationalisms in Early Twentieth-Century Cuba (2005); Visions of Power in Cuba: Revolution, Redemption, and Resistance, 1959–1971 (2012), which received the Latin American Studies Association‘s 2014 Bryce Wood Book Award; and Heroes, Martyrs, and Political Messiahs in Revolutionary Cuba, 1946–1958 (2018). You can read her article “Poder Negro in Revolutionary Cuba: Black Consciousness, Communism, and the Challenge of Solidarity” in HAHR 99.4.

1. How did you come to focus on Cuba as an area of research?

How could I not? To be honest, I spent most of my life as a kid trying to find answers to questions my Cuban parents did not even want me to ask, let alone want to answer. That is, as I discovered, a general rule of surviving the process of the Cuban Revolution and then surviving what it means to abandon that process, especially for Cubans in the United States—regardless of when they came or the contingencies that explain why they came. Today in my class for first-year students at UF, we were discussing Junot Díaz’s brilliant work, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, and I read a line from it that ultimately encapsulates why I “went deep” and decided to devote my life to learning about Cuba, from Cubans, mostly by going to Cuba. “But if these years have taught me anything it is this: you can never run away. Not ever. The only way out is in.” (page 209, by the way!)

2. Your article makes a fascinating contribution to a spate of new research on race and the resonance of the US civil rights movement in Cuba, some of which has been published in HAHR. What do you think has inspired this new research now? What inspired you to engage it?

The struggle for racial equality in Cuba was quintessential to the birth of cubanidad, and yet I was always fascinated and disgusted by the myriad ways that Cubans found surrogates and substitutes for openly endorsing racial equality. Indeed, Martí never came right out and said that he believed in black equality, despite the fact that some of his best buddies like Juan Gualberto Gómez did so. Gómez even had the audacity to title his newspaper La Igualdad under Spanish rule in the 1890s. From the time I first read Martí and, in 1991–92, researched what became two honors theses in college (one on Martí, the other on the Independent Party of Color and what I then called, pre–Aline Helg, “the Afro-Cuban Revolution of 1912”), I wanted to illuminate how and why white Cubans stood behind the discourse of racelessness in order to wield commitment to anti-imperialism as a club against those who demanded and deserved not only equality before the law but an open, publicly endorsed, government-sanctioned program for reversing centuries of discrimination and the legacies of slavery. By constantly citing the need for unity and the possibility that conflict would provoke another US intervention, Cuban politicians deliberately avoided having to change anything and ignored how claims of racelessness reproduced racism. Holding high that banner of “raceless” unity represented and promoted white supremacy. It still does. Years ago, when I was a student, famous historians shouted me down for using that terminology—white supremacy—to explain Cuban attitudes—and they weren’t just responding in the traditional fashion (more common then) of defending post-1959 Cuba unconditionally because of the aggression of the United States. It was as if Americans had a monopoly on deploying white supremacist ideology as well as a monopoly on defining its meaning.

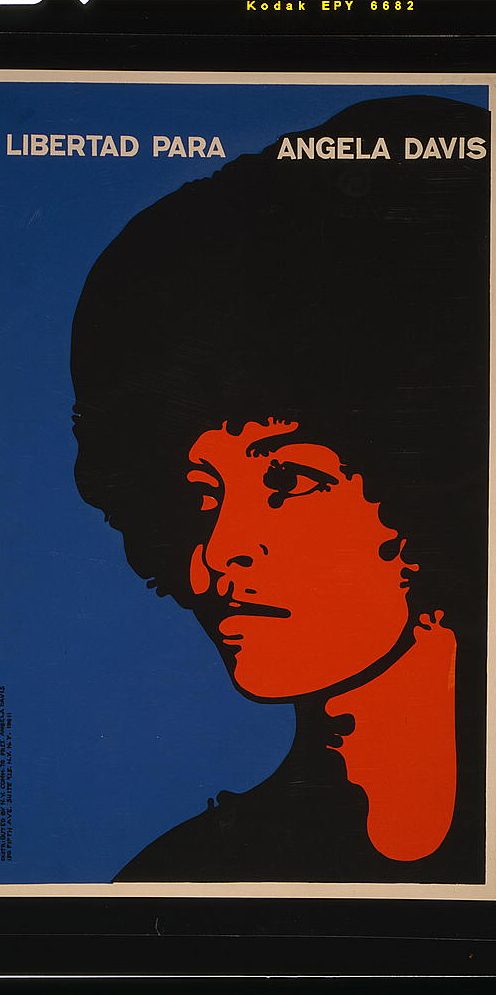

In my works on the Cuban Revolution, I have tried never to lose sight of race, the denial of racism in the guise of anti-imperialist nationalism or their importance to explaining Cuba’s political experience. I have wanted to explain race, like gender and class, as intimate, central dimensions to that experience. My approach has been to combine these dimensions into interpretations of Cuban history that reach far beyond any one of those concerns alone. For this article and the book of which it forms a part, I take on the centrality of the post-1959 government’s efforts to create and sustain the idea that the United States enjoys a monopoly on white supremacist ideology in order to secure and ensure belief in Communist Cuba’s exceptionality. The lengths to which the Cuban government went to depict the Civil Rights Movement in the United States as a morally admirable but ideologically confused approach to racial equality remain unknown for two reasons: first, because in the United States we simply didn’t want to know and preferred simple stories about what was happening in Cuba; second, because in Cuba the whole idea that black Cubans had anything to imitate, admire, or learn from US Black activism was politically anathema to the post-1959 Cuban state. It was also taboo to the political culture and white-dominated state far earlier than 1959. Taking on this history, I should say, is not easy today for the same reason that it was not easy for black Americans in the 1970s to admit openly their critiques, disappointment, or even outrage (as Eldridge Cleaver articulated to Skip Gates) over Cuba’s revolutionary regime. To do so was to take the side of the white imperialist power structure, and it was easier not to because one would then have to explain the contradictions and complexities. Explaining things is a burden but also a liberation.

3. What research challenges did you face in reconstructing this article’s transnational story of Black Power in the United States and Cuba?

I have spent years accumulating bits and pieces of different histories, and so being able to put the jigsaw of them together did not prove difficult once I started. I have here to rail against the use of digital sources, however, because one of the reasons I have been able to find so many bits and pieces of Cuba’s history has to do with my method: sitting at a table and going through an entire run of a Cuban magazine, for example, page by page, is essential to me. You can’t do that if you are sitting at a screen and using searchable pdfs to find only what you think you should find. You have to see where an article appears, the whole page, what other articles, ads, or images were published next to it. You also have to cast your net broadly. That means if you are in an archive and you happen upon a whole slew of documents that reveal something that appears tangentially related to what you want to find, you look at them anyway and you do your best to copy, photograph, or bring them home with you in tangible form so that you can do something with them someday. You have to let your sources rather than your desires drive your research and your arguments. This, in sum, is a challenging approach because it commits you to years of work, not to a single project but to many, all the time. Finally, I would say that I have come to believe with greater and greater faith in the idea that when people have suffered injustice and you are devoted to unearthing it and, at least in that way, righting their wrongs by telling their story, they don’t let you go. My grandmother used to say to me, “No hay nada eterno en esta vida, hija, sino la persona que tienes al lado” (There is nothing eternal in this life, daughter, except for the person sitting beside you). By that she meant that if we think there is no life after death, we are wrong. She also said that a lot because she had experienced great uprooting and traumas in her life that she never expected to experience: she wanted me to know that the material world is meaningless. So, in short, I believe in spirits, and incredibly, finding a lot of the best sources in this new work and my previous books can only be attributed to the intervention of ghosts! (Nothing more Caribbean or Catholic than that, by the way.)

4. Your article opens with fascinating anecdotes about how Cubans responded to race in the United States with the presidency of Barack Obama. How has this response changed, if at all, in the Trump era?

Cubans with whom I have met and discussed current conditions since 2016 have, to a one, been horrified by the turn back to the past that, first, the election of Trump, and, second, the return to hostility, isolation, and rejection has meant. The latter is a very comfortable place for the right-wing, officially pro-Trump exile community of South Florida to occupy, but it is also a very comfortable place for the Communist state of Cuba to inhabit. It leaves neither side accountable to the ideals of justice, democracy, or citizens’ right to represent and influence their respective states. For Cuba, the shift is tragic. Today, once again with no free or subsidized oil flowing into the island, daily struggle, hunger, and a state that monopolizes wealth and controls the economy are once again freezing Cubans in place politically. What has changed, however, is that as of 2016, thanks to Obama’s normalization of relations followed by Trump’s general whites-only, anti-immigrant policies, there is no longer a Cuban Adjustment Act in place: from 1966 to 2016, it provided refugee status to Cubans who arrived in the United States with virtually no questions asked and created a safety valve for dissent and discontent on the island. Pressure is building in Cuban society right now because there is simply no way out. People who might normally dream of leaving the island and spend their energies trying to do are having to stay. The militarization and surveillance of everyday existence on the island have also been on the rise under Raúl Castro and Díaz-Canel’s rule. Since the early 1990s, when the Cuban Communist state’s ideological legitimacy collapsed alongside the Soviet aid that enabled citizens’ material security, “everyday forms of resistance” and dissidence have defined island life in unprecedented ways. That space has been closing up for several years now as state leaders have become increasingly convinced that citizens pose a threat, not just to the economic control its Communist-led capitalist sector represents but to its political control over information, attitudes, and perceived reality. Where this will lead nobody knows. I say all of this as backdrop to the question of how Cubans’ perceptions of race and its role changed—temporarily, as it turns out—the stakes and nature of US-Cuban relations since 2014.

When he announced the opening of diplomatic relations with Cuba in December of that year, Barack Obama completely disarmed the Cuban state by turning the tables on its leaders’ expectations and pattern of anticipating and relying on US behavior to justify their own. Among the things that the collapse of Obama’s policy of engagement eliminated was the path to revitalizing a public, open discussion of the extent to which US blacks have a lot in common with people of color in Cuba. With the rise of hip-hop and rap on the island in the mid-1990s, the Cuban state suddenly faced a public, open discussion it did not expect and whose boundaries it could not control. The government then literally attempted to co-opt those boundaries and the content of the discussion by creating an official state institute of rap. Hip-hop and rap, like many other forms of popular culture on the island, remain nonetheless a vital space for debating the limits of “racelessness” and forging a comparative analysis of black freedom struggles and black oppression across American societies. What Obama brought to the table, however, was the question of black political representation and power in the Cuban state—where it is and whether there actually is any black political representation and power in the Cuban state at all. Unfortunately, Trump has created a kind of “told ya so” environment in which Cuban leaders can claim they were right all along—that Obama was insignificant and represented the illusion of change at home and abroad. Of course, they denigrated Obama using traditional forms of visual mockery, as Devyn Benson has pointed out, almost immediately after his historic visit to the island in March 2016. That fact reveals just what kind of threat Obama represented. After all, if the famously white supremacist Americans could elect a black president, why could the famously “race-blind” Cuban nation never do the same—let alone speak about electing anyone, for that matter?

5. Is this article is part of a broader research project? If so, would you mind expanding on this project?

Yes. Gisela Fosado, Duke University Press’s editor of the Latin American series, deserves a special thanks for believing in the value of that project and my ability to get it done—hopefully by the end of next year! It is a book I see as essential to understanding how the Cuban state constructed and relied on citizens in order to sustain a one-party, top-down system of rule. After 1959, the Cuban leadership gradually but surely eliminated and then criminalized the right to protest, dissent, and criticize Communism, state policies, and, most precisely in Cuba’s post-1975 legal codes, Cuba’s leaders themselves. According to the 1975 Cuban Constitution, only a Communist has the right to criticize a fellow Communist. Even today, less than 10 percent of citizens are members of the party, and all votes taken on any issue are supposed to be unanimous, whether in the workplace or a meeting of one’s local Committee for the Defense of the Revolution. From the 1960s through the early 1990s, leaders cited voluntarism and “belief in the Revolution” as the primary pillar of state legitimacy and stability. They argued, as Fidel did repeatedly, that the state did not need to censor anything because citizens “self-censored” willingly, so great was their love for the Revolution. Leaders also contended that surveillance and a system for the denunciation of doubters and critics were primarily outgrowths of citizens’ own desires to defend the state rather than of the state itself. Yet the government cultivated, encouraged, and rewarded surveillance and the policing of thought through its organizations, pedagogy, overt forms of repression, and a culture of siege that agencies of the Cuban state disseminated through affective means—such as music and literature produced and approved by the Ministry of the Armed Forces. My book examines the crafting of denialism, that is, how the state went about denying its need to control diversity of opinions or punish dissent. It also explores the function of denialism as a state of consciousness among average citizens. Officials relied on citizens’ belief that there was no opposition in Cuba to ensure that there was no opposition in Cuba. They did that by orchestrating displays of loyalty that served to intimidate and repress, such as occurred during the 1980 Mariel Boatlift when Committees for the Defense of the Revolution orchestrated mob violence and labeled it mítines de repudio (meetings of repudiation). Teachers recruited elementary schoolkids and neighbors to stage these mítines de repudio by surrounding the homes of those who registered to leave Cuba, chanting insults at them and throwing eggs, often for hours or, in some cases, even weeks at a time. These were regular, nightly neighborhood events that took place across the island from April to October 1980. I ask, What was it like to grow up in this Cuba? How did leaders go from “teaching the work of the Revolution” to repression and exclusion? Through unused archives and oral history, I delve into the mechanisms through which grassroots support was constructed and challenged. Finding that the burdens of revolutionary citizenship often blurred lines, I illuminate an ironically apolitical nation within the binary of patriot versus traitor: there, a creative, collective individualism thrived.

6. Read anything good recently?

YES! I read Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof’s Racial Migrations and loved it. I reread Edwidge Danticat’s The Farming of Bones and wept. I also have read Bonnie Lucero’s A Cuban City, Segregated, Jorge Giovanetti’s Black British Migrants in Cuba, Greg Beckett’s provocative There is No More Haiti (of course, he is wrong about that), and Lou Pérez’s Rice in the Time of Sugar. If you can believe it, I also Saint Therese of Lisieux’s famous autobiography for the first time.

Top image: Photo of Varadero, Cuba, 2015. Photograph by Vlad Podvorny, licensed under CC BY 2.0. (Find the original here.)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.