Interview with Daniel Mendiola, author of “The Founding and Fracturing of the Mosquito Confederation: Zambos, Tawiras, and New Archival Evidence, 1711–1791”

Daniel Mendiola is a faculty fellow at New York University. His research interests include borderlands, colonialism, and conquest, with Central America’s Afro-indigenous Mosquito confederation forming the principal topic of his dissertation and first book project. You can read his article “The Founding and Fracturing of the Mosquito Confederation: Zambos, Tawiras, and New Archival Evidence, 1711–1791” in HAHR 99.4.

1. How did you come to focus on the Mosquito Kingdom as an area of research?

I first arrived at this topic through my interest in colonial borderlands. I have long been inspired by stories of people who don’t fit neatly into the canonical grand narratives of the past, and this type of recovery lies at the heart of borderlands studies, which centers the peoples who inhabit spaces at the margins: usually physically in relation to territorial centers of power, but also the margins of national memories. From early in my graduate studies, I found myself drawn to borderlands research as an approach for rethinking who participated in colonial processes, how they participated, and to what ends.

However, whereas most borderlands studies have focus on the northern borderlands of New Spain in what is today the American Southwest, I began to wonder whether similar processes might have been happening in other parts of the Americas. Therefore, my research on the Mosquito Kingdom essentially began with the simple question: was colonial Central America also a borderland? Ultimately, the answer to this simple question is complex, with Central America paralleling other borderland regions in some important ways yet differing in many others. Nonetheless, this line of inquiry has demonstrated that the Mosquito Kingdom, as well as numerous go-betweens and free peoples who interacted with the kingdom, played a much bigger role in shaping Central American history than traditional narratives have realized.

2. What challenges are posed in reconstructing the history of the Mosquito Kingdom, and how did you address these?

The biggest challenge in studying the Mosquito Kingdom has always been the limited source base. There was no written form of the Miskitu language in the colonial period, so the Mosquito Kingdom did not leave its own written documents. Because of this, researchers have always had to rely on documents produced by English or Spanish officials who usually had little firsthand knowledge of the Mosquito Kingdom. Moreover, these sources appear only sporadically in the archives of major colonial centers, making it difficult to piece together a full narrative of chronological events.

When I visited the National Archive of Costa Rica (ANCR), however, I discovered a substantial body of documentation related to the Mosquito Kingdom that previous studies had not yet utilized. Since Costa Rica was one of the sites of most intense contact between the Mosquito Kingdom and the Spanish world, this documentation was consistent enough to piece together a relatively thorough, chronological narrative than possible in previous studies. Still more, these sources tended to be based on firsthand interactions, including numerous interviews with bilingual informants who spoke on behalf of Mosquito leaders, as well as telling their own experiences. Of course, these documents are still mediated by Spanish officials to some extent, so it is not the same as having a document written by the Mosquitos themselves. Nonetheless, these testimonies provide key insights into Mosquito practices that other sources simply cannot provide. In fact, ANCR sources have been so key to my research that I even wrote a full article for the 2018 issue of the ANCR’s own journal—the Revista del Archivo Nacional—describing the significance of the collections for studying the Mosquito Kingdom.

3. You mention that the history of the Mosquito Kingdom traced in your article “contributes a basis for reflecting on how the meanings of socially constructed differences such as ethnicity—differences that are not timeless or natural but emerge from specific historical circumstances—tend to change over time.” Would you mind expanding on these implications for broader historical research, in Latin America or otherwise?

I think one of the most fundamental purposes of historical research is to add context to the present, showing that the way things are now is neither timeless nor inevitable. Indeed, we know that the present is the result of dynamic, highly contingent processes, and documenting these processes encourages us to recognize that just as things were very different in the past, they can also be very different in the future. In other words, we do not have to passively accept the status quo as if it were natural or inevitable.

Race and ethnicity have long been important examples of why this approach to history matters. Whereas our particular ways of thinking about, performing, and experiencing race today may seem intuitive, history reminds us that race is historically constructed and therefore only means what we make it mean. The history of the Mosquito Kingdom provides an interesting example of this phenomenon since the confederation’s ethnic divisions took on a specific, divisive meaning in the nineteenth century after the civil war, yet it was not inevitable that ethnic distinctions would be a divisive force. In fact, before the civil war, ethnic divisions had meant something completely different.

Along with race, another topic in which contingency has become increasingly important to recognize is bordering. Whereas political discourses in 2019 tend to take it for granted that nations need “strong” borders and that a border’s strength is directly proportional to its capacity to regulate migration, this is a surprisingly recent way of thinking. Significantly, early national discourses barely made any connection between borders and migration, demonstrating that restricting migration is not a necessary component of the nation-state. Rather, it is part of a more recent logic that was added later. Recognizing this contingency, therefore, opens up a space to question border policies that our generation is starting to take for granted. Have these changes been for the better? And if not, what is stopping us from changing them?

4. What is the contemporary legacy of the Mosquito Kingdom, in Nicaragua or otherwise? How does centering the kingdom shift our understanding of the region or of Latin America, if at all?

In many ways, the Mosquito Coast continues to function as a colonial borderland. Whereas neatly drawn political maps suggest integrated national territories in Nicaragua and Honduras, the people of the region have maintained various degrees of autonomy. However, just as the concept of borderland remains relevant, so too does the concept of conquest. Sadly, the Nicaraguan and Honduran governments continue to treat the regions as frontiers to be closed in spite of offering some nominal recognitions. The violence of these conflicts was perhaps most visible to outsiders in the 1980s when numerous Miskitu communities clashed with the revolutionary Sandinista government, but it is important to note that conflicts continue. In 2019, for example, the Center for Justice and International Rights (CEJIL) released a report documenting how the Nicaraguan government has tacitly facilitated illegal settler projects that are gradually dispossessing the Miskitu of their lands.

Regarding the broader region of Latin America, I think this case is emblematic of broader trends in which the term conquest continued to be relevant long after independence. Much like the imperial projects that preceded them, American nations applied overt military campaigns, as well as more subtle projects of settler colonialism, in order to subjugate and dispossess indigenous peoples who had never lived under Spanish rule. In this sense, nation-states continued to act very much like empires, forcing us to grapple with question such as: To what extent is the classic division between the “colonial” and “modern” periods significant? For whom? And why or why not?

5. Is this article part of a broader project? If so, would you mind expanding on how the article fits in that project?

I am currently working on a book manuscript that offers a more comprehensive assessment of the Mosquito Kingdom and its influence on the history of Central America throughout the eighteenth century. Whereas the article focuses on introducing some foundational concepts for understanding Mosquito history such as the development of the confederation, the book tells a more detailed narrative. The influence of the borderlands approach is also more direct in the book, which treats colonial Central America as a site of three competing conquests: the Spanish, the English, and the Mosquito. Ultimately, the book tells the story of all three conquests, though at the same time keeping the Mosquitos themselves at the center of these narratives.

6. Read anything good recently?

For thinking broadly about the ongoing processes of imperialism and colonialism:

- James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed (2009)

- Ann Stoler, Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times (2016)

- Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire (2019)

For how these ongoing processes of imperialism and colonialism affect bordering and borderlands specifically:

- Carlos Sandoval, No More Walls: Exclusion and Forced Migration in Central America (2017)

- Jenna M. Loyd and Alison Mountz, Boats, Borders, and Bases: Race, the Cold War, and the Rise of Migration Detention in the United States (2018)

- David Scott FitzGerald, Refuge beyond Reach: How Rich Democracies Repel Asylum Seekers (2019)

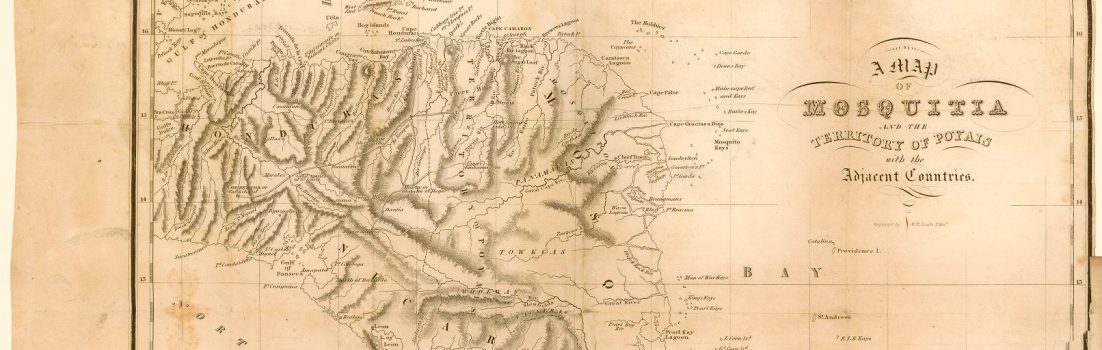

Top image: A map of Mosquitia, 1822. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. (Find the original here.)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.