Interview with Matthew Butler and Kevin D. Powell, authors of “Father, Where Art Thou? Catholic Priests and Mexico’s 1929 Relación de Sacerdotes”

Matthew Butler is an associate professor in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of numerous publications on the history of the Cristero movement and of Catholicism in Mexico and is currently finishing a book manuscript on the history of constitutional Catholicisms in modern Mexico.

Kevin D. Powell is a historian of Latin American religion and ideas. He received his MA at the University of Chicago in 2018. He is currently researching the transnational consolidation of networks of Catholic integralist lay movements in Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, and Chile and the emergence of the Latin American Anti-Communist Confederation.

You can read their article “Father, Where Art Thou? Catholic Priests and Mexico’s 1929 Relación de Sacerdotes“in HAHR 98.4.

1. How did you come to focus on Mexico as an area of research?

MB: I became interested in Mexico as a result of going there as a student to learn Spanish and being struck, like many other visitors, by the endless manifestations of public Catholicism on view. The existence of a massive popular church in a country with institutions built out of nationalistic struggles like the Reform and the Revolution creates a tension that has worked itself out historically in impassioned and sometimes tragic ways. As a graduate student I went to Michoacán to study the cristeros, and that was the beginning of a long fascination with Mexican religious and campesino history.

2. Your article centers around a 1929 survey from Mexico that helped end the Cristero War. How did you first come across this document? And when did you first realize its significance?

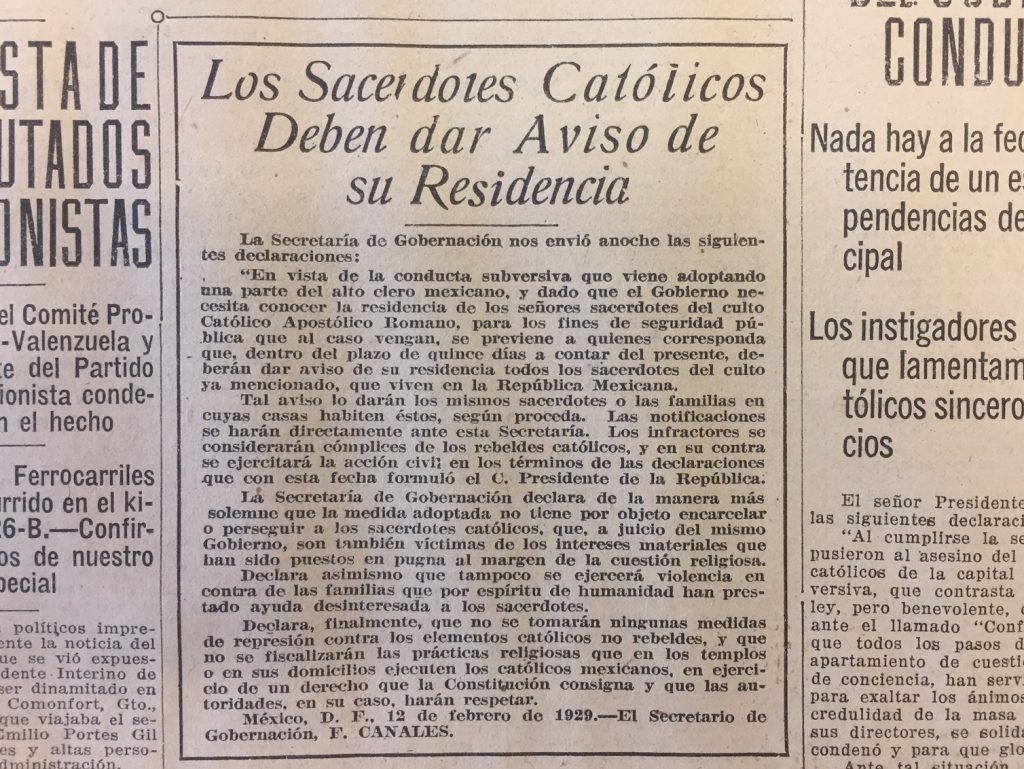

MB: The document turned up, misfiled and unexpectedly, in a box in the Interior Ministry gallery of the National General Archive in Mexico City. At the time I was searching for documents on dissident Catholic priests in Mexico, then out of a box fell what was clearly an important survey concerning the relationship of the official church to the state. It listed all the priests across Mexico who revealed their names and addresses to the state in 1929, rather than be qualified as rebels. I had seen this document mentioned before, but I don’t think anyone else had seen the census return itself, because it wasn’t where it was supposed to be. Usually the Relación was namechecked as just another piece of anticlerical bullying, a kind of forced revelation of identities and whereabouts. When I began studying it more closely with Kevin Powell, however, we could see that it was more than just a police control. Rather, the process of making the Relación involved a kind of functional negotiation between church and state. Really the making of the census was a way of quantifying support among priests for the softer religious policy of the Portes Gil government (1929–31) and the Catholic hierarchy’s decision to negotiate with Portes Gil. It was a creative instrument and a performance, not just a wanted list.

KP: Following on from this, I began researching the political context in Mexico City and Rome in which the Relación became meaningful. We had a state census of Catholic priests created just four months before the end of the Cristero War (June 1929), yet this was a conflict whose origins were to be found in priests’ very rejection three years earlier of another state-mandated registration project. There had been in the middle of the Cristero War one or two regional or state-based military-enforced priest registrations and relocation sweeps, and this made the volunteered 1929 registrations even more intriguing. A lot of things had to happen to get these priests to sign up for what may have looked like a trap at the beginning, even though it was really the means to move toward reconciliation and peace. It’s telling that when I went to the archive and searched through the newspapers the most difficult task wasn’t finding Relación-related articles themselves, though this was actually a pretty grueling exercise by itself. The hard part was consolidating the dozens of newspaper reports that covered these public declarations and learning to read these back-and-forth responses as priests and officials at the time would have read them, as signs, clues. Once I was familiar with the “code” of these public pronouncements it was easier to capture the link between the church-state truce of 1929 and the Relación. Basically the Relación provided a way for the regime to distinguish between loyal, censused priests and rebel priests, and for “patriotic,” peaceful clergy to stand up and be counted.

3. How does the negotiation and argument around this survey among government officials and Catholic clergy, chronicled in your article, inflect contemporary Catholicism and church-state relations in Mexico?

MB: My first visit to Mexico was a couple of years after the 1992 constitutional reforms that undid many of the revolutionary-era restrictions on the church and actualized the lay state in Mexico. Since then, however, hardly a month has gone by without the laicist character of the state being compromised in some way. One way of explaining the continued closeness between church and state and the many violations of strict laicism is that the church colonizes the state in order to cling to its remaining monopoly status. But the Mexican state also likes a loyal church with which it can deal and negotiate. This kind of quid pro quo is obviously a relic of Mexican Catholicism’s colonial foundations as a state religion. What’s interesting about the Relación document discussed in our article is that it shows how peace was restored to church-state relations after three years of intense conflict (1926–29) when elements of this historic relationship were renegotiated and rebuilt bureaucratically. The long-term default setting for church and state in Mexico has been one of mutual dependency. The Mexican Revolution menaced but ultimately reproduced that pattern, and the Relación helps us to see how that happened. Two quick examples from today. The president-elect, AMLO, in one of the presidential debates back in the summer, talked about inviting Pope Francis to participate in a national convention to discuss Mexico’s future. Just two days ago, an attempt was made to rob or maybe assassinate the former archbishop of Mexico, Norberto Rivera, at his home in Coyoacán in Mexico City, and a member of his police escort was killed in a shootout. The official response to this crime has been nothing short of remarkable. On the other hand, few archbishops of Mexico have been more loyal to the governing class than Rivera. Immediately, one of the questions that critical media outlets like Proceso focused on was why a former ecclesiastical dignitary should have received a Policía Bancaria e Industrial escort at all, like a public official.

4. What tips would you have for scholars hoping to engage in collaborative scholarship, such as this cowritten article?

KP: I don’t think that there really is or should be a kind of one-way, basic strategy to do it. There are technically as many different ways to go about a collaborative research project as there are combinations of different individuals and primary sources, and what our work system/dynamic was like may not necessarily work for others, though for projects similar to our own having from the outset a pretty distinct dividing line (not that this needs to be a strict two-way street in terms of work agendas) works toward making sure that each person has a pretty clear idea of their priorities. One component of the project was the actual investigation into the Relación’s coming to be and significance. This entailed a very careful search through several months of issues in two newspaper dailies for anything to do with the registration process. The second component was creating the statistical source, which required entering all the list info (over 1,000 priests’ names and addresses) into an Excel sheet and going through that probably about a dozen times with a fine-tooth comb to identify input errors and repetitive/missing information. This was followed by performing a number of statistical operations (often mini-projects in themselves). So what’s obviously key here is communication and making sure the other person is kept up to date on findings and progress made, ideas of course, mini-tasks going forward, problems, etc. I think I was probably overly communicative, though he didn’t seem to mind. I’d write pretty long emails to him that could consist of updating him on a task, sharing observations and ideas, asking questions, and arranging meetings to discuss the next step in the project. These meetings were spaced at two-week intervals, which was perfect as a weekly meeting would have been too much and one every month would have made the project move unnecessarily slower. I should add that the emails were also an excuse to flesh out individual ideas and conclusions, which probably helped us to not only stay on the same page throughout but were key to helping develop arguments, conclusions, statistical approaches and observations, and critical arguments that would later be articulated in the paper. Crucial to the success of a project of this kind is building and maintaining with the other person a collaborative relationship that is built on mutual respect and a genuine and deep interest in the material. But I think what can’t really be predicted or made to happen is the development of an intellectual camaraderie that also became an amistad forged by the mutual experience of overcoming the twist and turns of research, writing, and the publication process, when mental fist bumps become hurrahs.

5. Read anything good recently?

MB: Sarah Osten’s new book on the tropical revolutionaries of southern Mexico turns the microscope upside down and is going to change the way that we look at the origins of one-party rule in postrevolutionary Mexico. When it comes out, Brian Stauffer’s book on the Religionero rebellion in Michoacán is going to do something similar for the history of the Catholic Church in the nineteenth century and the roots of the Porfiriato. It’s been out for a couple of years, but Romana Falcón’s book on the Jefe Político is pretty monumental and revisionist, too.

Top image: New cathedral, Guadalupe, Mexico, 1898. From The New York Public Library (find the original here).