Interview with Jaymie Patricia Heilman, author of “Peruvian Cocaine Triangles: Arrests and Assertions of Innocence in Ayacucho’s Drug Trade, 1976-1981”

Jaymie Patricia Heilman is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Alberta. Her work focuses on indigenous political activism and radical politics in twentieth-century Peru. You can read her new article, “Peruvian Cocaine Triangles: Arrests and Assertions of Innocence in Ayacucho’s Drug Trade, 1976–1981,” in HAHR 98.2.

1. What got you interested in Peru as an area of research?

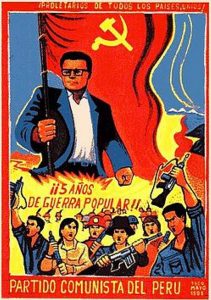

When I started my undergraduate history degree back in the 1990s, I was fascinated with Chinese history and particularly the years of the Cultural Revolution. I took Chinese history courses, but also grew increasingly interested in Latin American history and was really loving the process of learning Spanish. When I learned about Peru’s Maoist Shining Path, my interests converged.

2. While your new HAHR article shares with your first book the setting of Ayacucho, Peru, prior to the Shining Path’s emergence, the article focuses on drug trafficking and the police. What led you to take on this new focus?

About fifteen years ago, a friend and I were driving to a rural Ayacucho community when my friend asked, “Do you want to see the highway?” I had absolutely no idea what he meant, as I thought the unpaved, curving road we were slowly bumping along was the highway. After I agreed, my friend veered the truck off the road and across a grassy plain. After several minutes, we were suddenly driving down a beautifully paved, flat, and freshly painted stretch of road. It was a so-called narcopista—a landing strip for illicit cocaine flights. That detour set me on this new research path.

3. You vividly begin your article by recounting “stories shared with [you] in hushed tones” upon telling Ayacuchans that you were researching cocaine trafficking and arrests in the region. Did such a taboo subject raise any particular research challenges, and if so, how did you overcome them?

Oral history has long been central to my research. Both of my books draw extensively on archival research and oral history interviews, and I am deeply committed to oral history as an essential research practice for historians. That said, I did not do oral history interviews for this article. The possible risks to interviewees—and, potentially, myself—seemed too great. I also wrestled for months with the question of whether or not to include photographs of arrestees in my article, especially given that these people so fervently stressed their innocence of cocaine-related crimes. In the end, after many conversations with trusted colleagues and friends, I decided to include photographs in this article, as I emphasize that these photographs were all carefully staged by police.

4. In what ways does your work challenge or clarify popular conceptions/misconceptions of the drug trade in Latin America, such as in Netflix’s series Narcos?

Sensationalized portrayals of narcotraffickers almost always ignore the marginalized men, women, and kids who labor in the lowest echelons of the illicit drug economy and who are routinely harmed by state-sponsored repression of that economy. Those are the people who suffer most, and who lose the most, and they are the kinds of people I talk about in this article.

5. In your author bio you mention that you are currently researching the history of drugs throughout twentieth-century Latin America. What encouraged you to shift from Peru to research the entirety of Latin America? Does your study of Peruvian history in any way inflect how you look at Latin America more broadly?

I have been teaching a course on the Global History of Illicit Drugs for several years now, and have benefited enormously from reading—and having my students read—David Courtwright’s book Forces of Habit. But as I developed an upper-level course on the History of Illicit Drugs in Latin America, I was not able to find a comparable book for the Latin American and Caribbean context. There is amazing work on drug histories in many different Latin American and Caribbean countries, but very little that attempts a larger, regional synthesis that is historical in focus. So, I decided to write that book myself.

It was through my work on Peru that I came to understand just how extensively anti-Indigenous racism has shaped national, regional, and local histories. I hope that I will be able to bring the same kind of attention to race and racism into my consideration of the broader Latin American context.

6. Read anything good recently?

I’m a big fan of historian Lina Britto’s work and am eagerly awaiting her book on the history of marijuana in Colombia. I recently had students in my History of Illicit Drugs in Latin America course read her NACLA article on the Netflix series Narcos, and a fabulous discussion ensued. When people ask my opinion of the show, I always tell them to go read Britto’s article.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.