Interview with Pablo Miguel Sierra Silva, author of “Afro-Mexican Women in Saint-Domingue: Piracy, Captivity, and Community in the 1680s and 1690s”

Pablo Miguel Sierra Silva is assistant professor of history at the University of Rochester. He is the author of Urban Slavery in Colonial Mexico: Puebla de los Ángeles, 1531–1700 (Cambridge University Press, 2018). His research is centered on the experiences of enslaved people, mostly Africans, South Asians and their descendants, in the cities of colonial Mexico (New Spain) during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. You can read his article “Afro-Mexican Women in Saint-Domingue: Piracy, Captivity, and Community in the 1680s and 1690s” in HAHR 100:1.

1. How did you come to focus on seventeenth-century Mexico as an area of research?

When I started my PhD at UCLA, I realized that most of the research on the African diaspora in Mexico and other Spanish American colonies focused on the years of the Iberian Union (1580–1640). The Afro-Mexican history of the mid- and late seventeenth century, however, had not been sufficiently studied, and this was especially true for the city of Puebla. I increasingly found myself drawn to this history for the decades after Portuguese independence, when Lusophone slaving networks were disrupted. I wondered, “What did the sudden rupture of the transatlantic slave trade mean for black communities in colonial Mexico, specifically in cities?” Cities in Mexico grew rapidly during the mid-seventeenth century, so I became interested in understanding specific urban spaces that Afro-Mexicans were forced to navigate during those years: the convent, the textile mill, and the marketplace. The black communities inhabiting these spaces became the focus of my first book.

2. How did the lack of pre-1700 records in Veracruz’s archives influence the questions you were or were not able to ask? What methods or sources did you employ to address the silences of the archives?

Studying seventeenth-century Veracruz presented a very different challenge compared to my research on Puebla. In the latter, I studied a highland city with an almost inexhaustible amount of local church and notarial records. Pre-1700 Veracruz, by contrast, requires delving into external archives and manuscript collections. Seville, Paris, Mexico City, to name a few locations, hold the historical fragments that inform life in Mexico’s most important Atlantic port. Whereas in my previous project I was concerned with producing robust information and trends, I am now more interested in highlighting archival threads that may speak to the individual experiences of the people kidnapped and dispersed from Veracruz in 1683. The intent is to apply microhistorical methods and concerns in order to arrive at personal motivations under the most dire circumstances, in this case a pirate raid. Centering the stolen women that did surface in the Saint-Domingue records allows us to interrogate the “bundle of silences” that have otherwise obscured their historical significance. As you might imagine, Michel Rolph-Trouillot’s Silencing the Past has been instrumental to this project.

3. Did you find any particularly compelling cases or life stories while researching this article?

Yes, of course! Virtually every case is remarkable in that buccaneer captives rarely leave archival traces. If I had to pick one life story, I would say that the case of Thérése Quadrat (likely, Teresa Cuadrado) is especially noteworthy. As a woman of African descent stolen from her native Veracruz, she survived the carnage of the raid and the forced voyage to Saint-Domingue. She would eventually marry in the French territory and have ten children (!) with Guillaume Boursicot. Quadrat would also become godmother to the infant Nicolás Trouvé. As a godmother, spouse, mother, survivor, she represents a different kind of seminal figure through which to understand the late seventeenth-century Caribbean and the emerging mixed-race population of early Saint-Domingue. Her story entwines the heavy, colonial legacy of Mexico and Haiti. I hope to learn more about her life and children for my new book project.

4. How did marriages and baptisms contribute to the development of a “paradoxical freedom” for the kidnapped Afro-Veracruzanas in Saint-Domingue?

When I began the research for this article, I did not understand the significance of baptism and marriage in early Saint-Domingue. In Mexico, the children of enslaved mothers were commonly baptized and marked as slaves within the very documents that marked their entry into Catholicism. This was not the case in Saint-Domingue, where baptism could operate as a liberating mechanism for the children of enslaved women in the late seventeenth century. The Code Noir of 1685, an otherwise dehumanizing document, also had a profound effect on unions between enslaved women of African descent and their French spouses. The code enabled these captive women to become free people through the acknowledgment of their sexual and domestic interactions with the buccaneers, slave traders, and early planters of Saint-Domingue.

5. How did Afro-Veracruzanas develop new lives and kinship networks in Saint-Domingue after the violence of captivity? Were legal and social factors in Saint-Domingue more or less flexible than in Veracruz and New Spain to allow these women greater flexibility to navigate their new realities?

These wonderful questions are some of the driving elements for my new book project. Afro-Veracruzanas definitely wove complex kinship networks in a French territory that was largely defined by the absence of European women and the constant arrival of enslaved Caribbean and African women. For instance, we know that the women of Veracruz interacted and befriended Mayan women from the Yucatán peninsula and other African-descended captives from Cartagena de Indias and Havana. Itinerant missionaries in Saint-Domingue formally recognized the Afro-Veracruzanas as marriage witnesses and comadres. This marked them as crucial participants in a frontier-island Catholicism we don’t know too much about. I do think that those Afro-Veracruzanas who secured their freedom encountered a more flexible society in the days before sugarcane cultivation monopolized Saint-Domingue, especially in the southern settlements of Petit-Goave and Leogane. But what of those who remained enslaved after the raid? Their experiences deserve much greater study.

6. Read anything good recently?

Yes! I just finished Fatou Diome’s The Belly of the Atlantic, on Senegalese migration to France in the early 2000s. I’m now reading another novel, Las mujeres de la tormenta, by Celia del Palacio. It’s a wonderful, imaginative account of six women’s lives in Xalapa, Mexico City, and Veracruz from colonial times to the present. (I try to read as much fiction as possible during summer.) Also, I would highly recommend Brenda Elsey and Joshua Nadel’s Futbolera: A History of Women and Sports in Latin America. I learned so much about the 1971 Women’s World Cup!

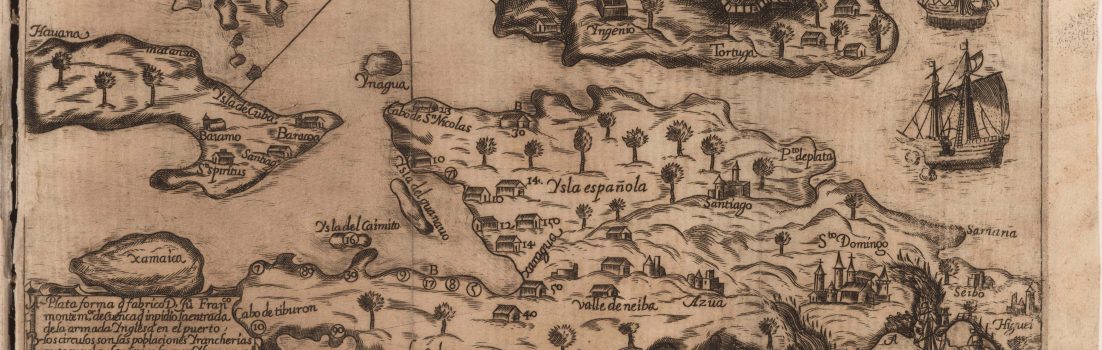

Top image: Plata forma q[ue] fabrico D. Ju[an] Fran[sis]co montem[ay]or de Cuenca, 1658. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. (Find the original here. Image MB size was adjusted.)