100 Years of HAHR: An Interview with John French, former senior editor

John French is a professor of history and African and African American studies at Duke University. He has published on to class, race, and politics in Brazil, Latin America, and beyond through 42 refereed articles and 3 books: The Brazilian Workers’ ABC (1992), Drowning in Laws (2004), and the coedited volume The Gendered Worlds of Latin American Women Workers (1997). This interview is part of a broader collection of interviews with previous editors of HAHR in celebration of the journal’s 100th anniversary. French was a former senior editor of HAHR when the editorial office was at Duke University (2012–2017) and a Book Review Editor when the editorial office was at Florida International University.

1. When did you first encounter the Hispanic American Historical Review?

Given the hackneyed commonplace about old horses and new tricks, too few people consider that young horses desperately need to master “tricks” they may think are old or dated. This is the contribution of a top-rate journal like HAHR: to put on offer the best of current research—in its diversity of chronologies, foci, and methodological orientations—thus adding to the archive that allows the newly trained to position themselves securely within the global development of our discipline and field of inquiry.

I believe much is lost when you publish in or follow only specialized journals reflecting your particular specialty. Moreover, there is a loss to the transition to the unbundled format in which search mechanisms deliver you to the specific subject you are looking for rather than browsing and reading the physical journal as a historical gestalt that, followed issue by issue, forces you to grapple with “what is the state of historical knowledge and technique at this moment in time?” As a young historian, I read HAHR cover-to-cover including and especially the reviews, and eagerly built up a collection of past HAHR volumes from retiring senior professors. By happenstance, I would find things I did not expect from my browsing given the presentism that characterizes the young, in training, who are absolutely convinced of the superiority of the new and novel and convinced that the past is mostly backwardness. The HAHR is an essential tool that assists a historian to achieve a depth of reflexive self-awareness of past and present best practice.

2. What made you decide to apply for the journal’s editorship? What had you hoped to accomplish as a senior editor?

I was involved in a bid for HAHR as an untenured assistant professor at Florida International University in the early 1990s and served a year as book review editor, a much harder job in a time when potential reviewers were to be found in yellowing index cards. Working under Mark D. Szuchman, the experience convinced me of inestimable contributions—which go well beyond shepherding a piece of scholarship into print—made by good editors and creative editorial teams. At their best, they collaborate with their colleagues by helping them to sharpen their focus, tighten their arguments, and broaden their historiographical contextualization while rethinking their train of causal inference from the evidence.

Once your article is accepted for external review (itself an achievement), scholars often have mixed feelings about strong editors and demanding editorial processes; as we know, it is sometimes easier to get a book published than an article in a top journal. But when I think about my first HAHR article, back in 1988, I realize how much I gained on every level ranging from citation format to the need to make my specialized piece speak to a broader audience of professional historians of the region. When I think about my last experience, in 2010, the reorganization of the article the editors suggested resulted in a leap in the coherence and power of the overall argument. So, when I am asked what I hoped to achieve working as co-editor with Jolie and Pete for five years, it was to offer a similar degree of exquisite engagement and rigorous attention to those practicing Latin American history today and thus keep the field moving forward.

HAHR Covers from Dr. French’s Tenure as Senior Editor

[SlideDeck2 id=2904]

3. As one of the senior editors of the Hispanic American Historical Review as it approached its 100th anniversary, you published research on the journal’s beginnings. Can you tell us a little about how the journal started? Did it face any particular challenges getting off the ground?

One of my treasured experiences as HAHR editor was to participate in the Encuentro Internacional “Las Revistas de Historia en la Consolidacion de la Disciplina en Ibero-America” held in August 2013 at the Universidad Nacional de Bogotá under the leadership of Dr. Mauricio Archila. This was the second of two such meetings—the first was in Mexico City in 2010—that brought together editors from dozens of history journals from throughout Latin America (the declarations of Mexico City and Bogotá continue to be relevant in articulating common concerns). As the only non–Latin American journal invited, HAHR’s editors were proud to be part of a hemispheric-wide gathering of professional historians like the one in 1916 in Buenos Aires that inspired the U.S. representatives to call for the founding of HAHR, one of the earliest specialized historical journals in the US.

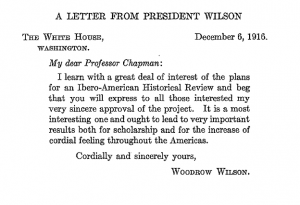

4. One bizarre feature of HAHR’s first issue is that it contains a letter from Woodrow Wilson supporting the journal. Can you say a little about the ideological and geopolitical trends amid which the journal first arose?

For all the structuring inequalities and scholarly malpractices of the past, the professional historians of the Americas—and the wider world—share a common and evolving disciplinary foundation and a shared ethics. This allows for the working out of differences of interpretation as part of a nationally, culturally, racially, and linguistically sensitive cosmopolitan pursuit of an ever fuller, more honest, and more powerful explanation of our respective worlds. Historians more than any other discipline should concern themselves reflexively with the constitution and evolution of our common pursuit as it is placed within existing structures of power. As I explain in my article, the scholarly activism of HAHR founders reflected the opportunities offered by the shift from Anglo-Saxonism to Pan Americanism in U.S. diplomatic and intellectual affairs, having already moved away from the Hispanism that first drew U.S. interest to Iberian worlds on both sides of the Atlantic.

5. Say that a historian 100 years from now were to consider the journal as it is today. What would they say about the changed ideological and geopolitical place of the journal? In other words, how has the journal’s role changed in the intervening 100 years from 1918?

Having already rejected the Protestant “Black legend” about Spain, the intellectuals who founded HAHR could be seen to be struggling—within the limits of the prevailing world view of their day—to transcend U.S. religious and nationalist prejudices by creating common ground across the Anglo/Iberian divide through an emphasis on shared liberal and republican values. In this regard, the newly emerging professional community of HAHR would provide—in the face of the ongoing imperialist follies from 1898 to the withdrawal of the Marines from Nicaragua in 1933—sustenance for the “Good Neighbor” as well as the tighter cooperation within the Americas during the war against fascism, Nazism, and Japanese militarism. The exercise of power and its ramifications, direct or indirect, have inescapable ramifications in the work of intellectuals. It is our common task to historicize our knowledge production to go beyond our past blindness—racial, gendered, and cultural—as part of an honest effort to understand and explain what truly makes the world tick. This strong but considered work is the best antidote to the aggressive unilateralism, racism, and cultural disdain still inscribed within the U.S. social formation and our current presidential administration in Washington.