Interview with Anne Eller, author of “Raining Blood: Spiritual Power, Gendered Violence, and Anticolonial Lives in the Nineteenth-Century Dominican Borderlands”

Anne Eller is an associate professor of history and an affiliate professor of Spanish and Portuguese at Yale University. She is the author of We Dream Together: Dominican Independence, Haiti, and the Fight for Caribbean Freedom (Duke University Press, 2016), which details the Dominican independence fight from renewed Spanish occupation (1861–65). She is currently writing a history of Caribbean politics in the 1890s. You can read her article “Raining Blood: Spiritual Power, Gendered Violence, and Anticolonial Lives in the Nineteenth-Century Dominican Borderlands” in HAHR 99.3.

1. How did you come to focus on the Dominican borderlands as an area of research?

The topic of “the border” looms over Dominican history, in part because of the genocide perpetrated by the state in 1937 against those thought to be Haitian or of Haitian descent. There has been really important research on this topic, including by Edward Paulino, by Lauren Derby, and a HAHR piece by Richard Turits. In the deep wake of that violence, as well as the present-day injustices perpetrated by the Dominican state, the long history of the borderlands is sometimes muted. Just like nineteenth-century borderlands studies elsewhere in the Americas, however, so many truths are revealed in these histories as the state slowly grows stronger. In my current book project, I am trying to approach popular politics in the 1890s, and I found a multiplicity of different narratives that emerge from these borderlands communities! Of course, foreign commentators hoped for conflict between the two states, often salaciously. And of course, too, Haitian and Dominican leaders targeted the areas, usually in vain, in attempts to expand the reach of the state. Surprisingly, however, the political goals of many living in center-island areas were often strikingly similar to deeply cosmopolitan and radicalized seaside towns (for example, Monte Cristi and Puerto Plata). Clearly the conversations in the 1890s were not about local conflict but rather the urgency of solidarity and political protest.

2. You strikingly note that “details about most of the rebels” covered in your article “appear in a perfect absence.” Would you mind expanding on how you dealt with the challenges of tracking down such “fugitive history”?

Many mysteries remain and simply refuse to be tracked. I am so indebted to scholars who have thought about these challenges in other contexts. For example, Marisa Fuentes, Stephanie Smallwood, Jennifer Morgan, Ada Ferrer, and others offer invaluable theoretical, archival, and methodological interventions. One of the hardest tasks is to layer a gendered analysis onto the praxis and experience of fighting. Here, too, I look to scholars of slavery, for example, Aisha Finch’s wonderful first book. Jessica Krug’s recent contributions to our understanding of fugitive politics, as well as her framework for understanding the “reputational geography” of an area like these borderlands, are also really key. Other than that inspiration, I only recommend dogged patience and persistence! The briefest of mentions in historical dictionaries, published local histories, or fragments of poetry: all are in here. I agree with many scholars who insist on the importance of speculation in these contexts, and I also think one starts to get an idea about remarkable common political understandings in the center island through a purposefully longitudinal view.

3. Your article consistently refers to the Dominican-Haitian border as the “center island.” What is gained by this conceptual move?

I wanted to think with a term that insistently highlighted not just lack of a physical or a thoroughly policed border (without even so much as military outpost, in most sites) but also the concrete existence of flowering human-commercial circuits favored by geography, of direct swaths of communication through valleys and key highland passes (and arid expanses, especially in the north). Residents and travelers experienced these areas as having strong nodal connections to other valley towns and, probably, in a somewhat more distant sense, to Port-au-Prince. They lived in a world unto themselves at times. I sometimes use “borderlands” in-text to highlight the area’s liminality to both capitals, a space that national politicians politicized and projected upon. But lack of national control over the center island and the existence of different affective, quotidian, and political communities constitute the fundament of the story.

4. Your article traces the many invocations of spiritual power during the armed mobilizations in the late nineteenth-century Dominican Republic’s borderlands. What conceptual challenges, if any, did you face in addressing these invocations, and how did you deal with them?

I try to heed scholars like Milagros Ricourt in thinking through how spiritual assertions of belonging and authority in rural Santo Domingo and the center island were expressions not only of some sort of millenarian crisis at different moments but rather constitutive of whole logics of community, expectations for an appropriate ordering of authority, and a common vocabulary of place—physically rooted in the local geography itself—that need great care and time in elaboration. The challenges are myriad in reconstructing these stories! I look forward to reading forthcoming work by Aida Heredia, Christina Davidson, and others, who are going to enrich our understanding of the rich spiritual-political landscape of the nineteenth century.

5. What contemporary resonances, if any, do you see for the nineteenth-century Dominican-Haitian interactions carefully narrated in your article?

Just as President Heureaux’s real problem along the “border” in the 1890s was not any sort of national enmity but rather the rebels who opposed him there, so do some present-day Dominican politicians invoke anti-Haitian discourses as a blatant and cynical distraction from other issues. Without speaking for others in the present day, I will note that activists, scholars, and others, both in diaspora and on the island, insistently call out this diversionary and racist tactic. And, they offer urgent counternarratives that reject the conflict framework for what it has always been, a malicious and unrealized project.

6. Read anything good recently?

I just finished reading Dixa Ramírez’s moving and provocative article “Mushrooms and Mischief,” and I am so excited to begin Caree Banton’s More Auspicious Shores!

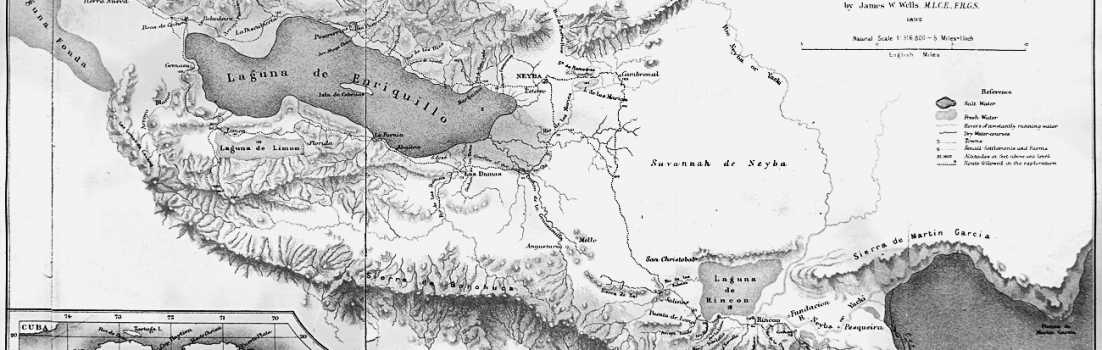

Top image: “Sketch Map of the Country between the Bay of Neyba and Laguna Fonda in the Republic of Santo Domingo, by James W. Wells, MICE, FRGS, 1892.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.